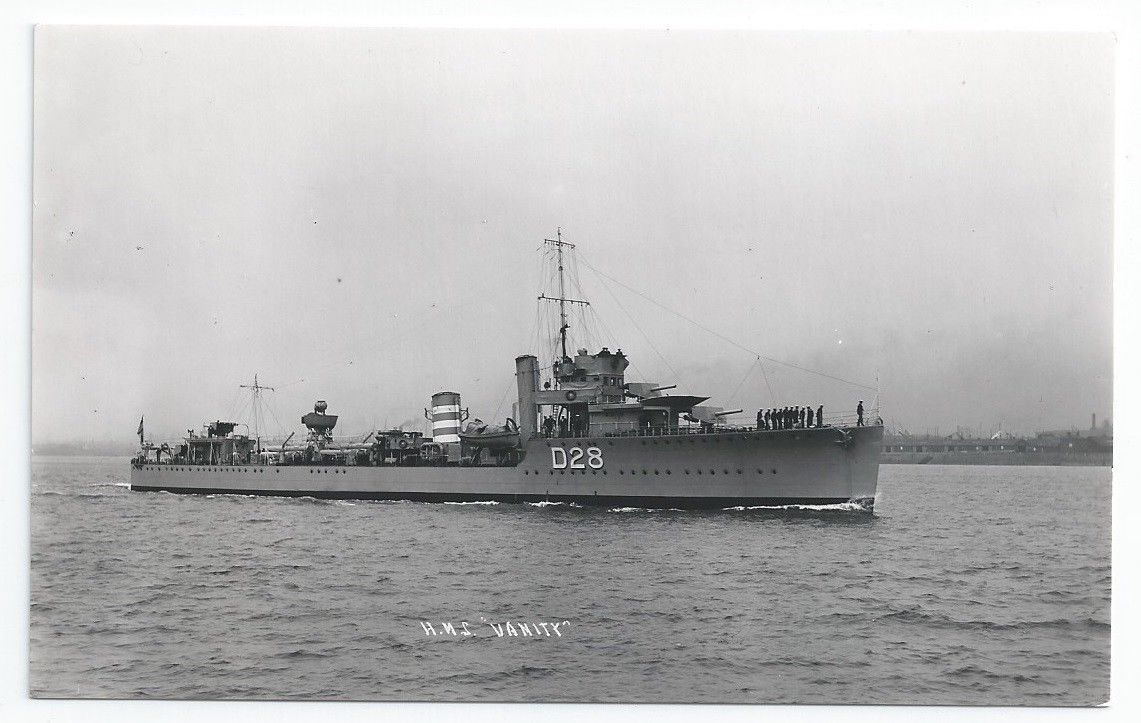

Winteringham

is a small village one mile south of the Humber and eight miles north

of Scunthorpe, the muncipal borough which adopted HMS Vanity after a successful Warships Week in December 1941.

But everybody living in Winteringham knows that she is their warship,

not Scunthorpe's, and there is a scroll hanging on the wall of their

village hall to prove it.

On 10 June

1995 Ken Ashton, a local historian in Winteringham, wrote to his Member of

Parliament, Elliott Morley, enquiring about the adoption of HMS Vanity

by Winteringham. Morley passed on his enquiry to the Hon

Nicholas Soames MP, the Minister of State for the Armed Forces from

1994 to 1997, in the government of John Major. Nicholas Soames made

enquiries and sent a very helpful reply in which he wrote:

"HMS Vanity

was into an anti-aircraft escort vessel, recommissioned on 12 August

1940. Virtually all her subsequent career was spent with the Rosyth

Escort Group on East Coast convoys from the Firth of Forth to the

Thames (the FS series) and back again (FN series). It was a vital if

unglamorous role and most of the convoys passed unharmed, only 171

ships out of 104,792 escorted in 3,584 FS/FN convoys being lost.

In December 1944 the Vanity was rendered non-operational after colliding in fog with the merchant ship Apex.

She went to Antwerp for repairs and in June 1945 was disarmed and went

into reserve for the last time at Grangemouth. She was sold for

breaking up in March 1947."

Lt S J Beadell, RNVR, (SP), an official Naval Photographers, spent some time in HMS Vanity in

October 1940 and his fine photographs are in the collection of the

Imperial War Museum in London. They are all Crown Coopyright which has

long since expired and the IWM permit their use on not for profit

websites such as this. Some appear on this page with their IWM

reference to enable high resolution prints to be ordered from the IWM.

Ken Ashton arranged for the scroll awarded on the adoption of HMS Vanity

by Winteringham and the letter from Nicolas Soames and other related

documents to be framed and hung in the Village Hall where they can

still be seen today. Nicholas Soames included with his letter a list of convoys escorted by HMS Vanity and the National Archives ADM reference for the Reports of Proceedings written by the CO of HMS Vanity when Vanity

was the Leader of the Escort Force and he was the Senior Officer.

These documents are linked to from this

page as PDFs as an aid to future research in the National Archives at Kew.

In 2017 the Winterton Probus Club invited Havard Phillips, a 92 year old former RDF operator in HMS Vanity,

to talk about his wartime service at a lunch time meeting in the Bay

Horse Inn at Winteringham on 12 September. Afterwards, David Malcolm

talked about his father's memories of serving with Havard as an RDF

Operator in Vanity.

It was a very successful meeting and I have been sent a copy of

Havard's talk by the meeting organiser, Martin Bell, and it is

published below by kind consent of Havard's daughter, Anne McDowell.

Sadly, her father William Lewis Havard Phillips, died on 24 October

1919 aged 94.

**************

Memories of my time on HMS Vanity

Havard Phillips, wartime RDF (Radar) Operator in Vanity

These memories of my time as radar operator on HMS Vanity

span the period of two and half years during the last war. 70 years

have elapsed since then and it is poignant to remember that most of the

people I served with and fought are now deceased and importantly their

descendants are no longer enemies but allies and friends.

These memories of my time as radar operator on HMS Vanity

span the period of two and half years during the last war. 70 years

have elapsed since then and it is poignant to remember that most of the

people I served with and fought are now deceased and importantly their

descendants are no longer enemies but allies and friends.

I was brought up near Swansea and from an early age I loved the sea. I

can remember in the late 1930’s my father taking me to the docks to see

a British warship and it was something I never forgot. When I was

seventeen and half I volunteered and had no hesitation in joining the

navy, it was like a calling and HMS Vanity soon became my home.

The ship was built in 1918 as the Great War came to an end. She was

brought into action again along with a number of others of the same

class in 1940 to escort convoys of merchant ships bringing military

equipment, food and other things the country needed from all parts of

the world. The ship was built for a crew of 90 but the enhanced

equipment by 1940 needed a crew of 110 plus. This meant that the living

conditions were somewhat cramped and primitive. Even so she was a very

happy ship and the crew was most loyal to the cause.

HMS Vanity along with many

other vessels operated from the naval base at Rosyth on the Firth of

Forth, this location, being strategically located to cover the North

Atlantic route to Russia and the whole of the North Sea. Convoys of

ships were formed at the mouth of the Firth of Forth under the

protection of the navy who then travelled North, South and East.

British armed forces needed vast amounts of equipment in advance of the

invasion of Europe. Most of this came in ships coming from North

America and the rest of the world and the North Sea route was

considered the safest route compared with the South Atlantic where the

enemy operated their U boats warships and aircraft.

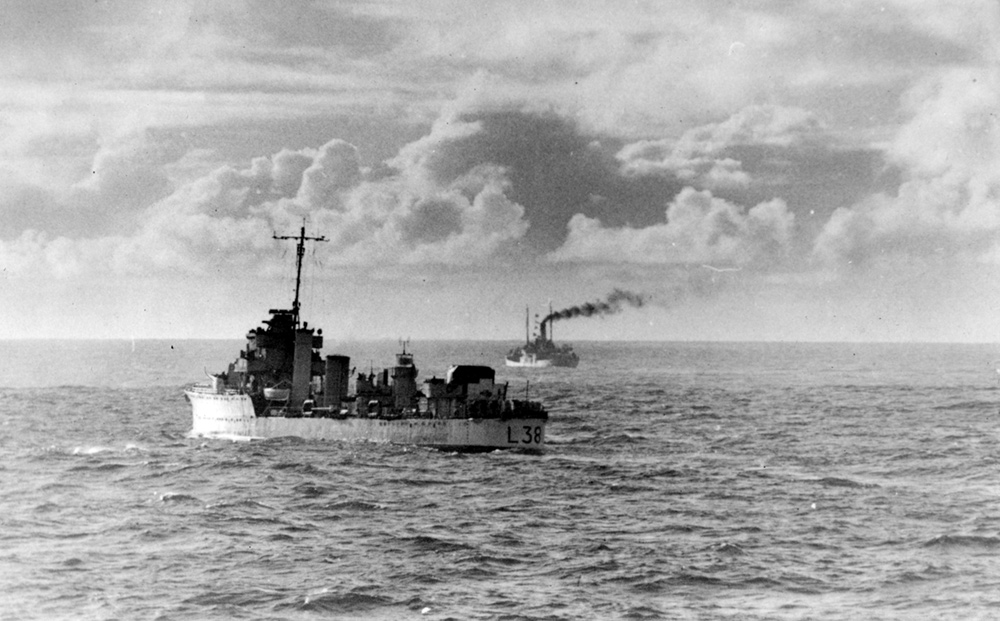

Firth of Forth to the Thames estuary

HMS Vanity was mainly

committed to escorting convoys between the Firth of Forth and the

Thames Estuary. Convoys assembled in the mouth of the Firth of Forth

and would typically be escorted by three naval ships. One to lead, one

to follow and the third with a roving remit. The merchant ships varied

in size from the biggest Liberty ships down to small coasters and speed

varied from as low as 20 knots up to as much as 40 knots. The smaller

ships were usually coasters carrying coal from the Durham and Yorkshire

coalfields to London and the south of England.

These voyages took two days in both directions. Going south the first

day was travelling over deep water from the Firth to the Humber. It was

in these waters that the enemy patrolled with their fleet of U boats.

On the second day we sailed from the Humber to the Thames and this leg

of the journey presented a different challenge. The convoy passed

through “E-Boat Alley” a channel of shallow water between the east

coast and Dogger Bank. This channel was marked by physical buoys which

appeared on navigation charts and were easily identified by radar.

However the E-boats would tie up to the buoys and could not be seen

until they separated and one echo turned to two. E-boats, were small

extremely fast craft powered with aircraft engines and equipped with

light armaments similar to our Motor Torpedo Boats. As a consequence,

they found it easy to outmanoeuvre a destroyer like the Vanity.

Our superiority came from our fire-power and ability to outgun the

E-boat. Despite these hazards our convoys had a great record of getting

their ships safely to their destination.

The convoy was typically dismantled on the Thames and usually the

ship’s crew had a welcome night ashore before making the return journey

back to the Firth of Forth.

HMS Vanity remained unscathed

during my time aboard and I was not aware of any casualties other than

on one occasion when we picked up two German bodies probable from the

crew of a sunken U boat.

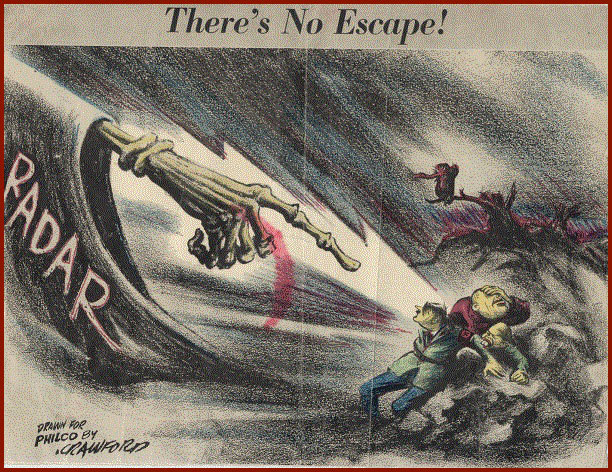

My job as a radar operator

I was too young to become an officer but because I had O levels I

qualified to become a radar operator. The course lasted about three

months and took place around the Isle of Man. The training took place

on a ferry type ship which had been commissioned for the purpose and

had been specially equipped with radar and other teaching aids.

Radar in those days was very primitive and incorporated cathode ray

tubes. One model was for surface radar (No S271) and the other for

aircraft (No 291) and in both cases the aerials were rotated manually

which is hard to believe given the sophistication of today’s

technology. The equipment was housed in a small cabin and the operator

was required to inform the officer in charge of any activity

identified, giving the direction and distance of the object and a guess

as to what it might be. It won’t come as any surprise that the job was

largely monotonous and hard on the eyes. The times it became exciting

were few and far between, but when action happened the adrenalin kicked

in and it became very exciting.

You had to laugh

I remember when Vanity was

sent to the North Atlantic to escort a huge merchant ship back to Scapa

Flow. It was blowing a gale and the sea was very rough. Vanity

could only keep the same speed as the merchant ship by sailing at full

speed, driving the bow hard into the waves and shipping water below

decks. It took weeks to dry out the living quarters.

On another occasion we were involved in escorting a convoy half way to

Russia. Neither the ship nor the crew were properly equipped for the

job. The cold was unbearable and the ship’s company were enormously

relieved to learn that the mission was a one off never to be repeated

again.

We also experienced a “navy lark moment” when Vanity

had to be taken into dry dock in Antwerp to repair damage to a

propeller. I and others were led to understand that the damage was

caused by a limpet mine picked up in the channel - or this was the

official line. Those in the know knew that the damage was caused by a

collision - all I can say is - I was there!

"Some of my friends and shipmates in Vanity"

"Some of my friends and shipmates in Vanity"

Back row: John Malcolm (third from left), Jack Hickman (third right) and Paddy Dalton (second right)

Front row: Jock MacGowan (second left) and a young Havard Phillips (right end)

Courtesy of David Malcolm

Life aboard

The crew of a ship had three levels of rank, officers and

non-commissioned officers and ratings. In contrast with civilian life

men from a whole range of backgrounds lived together in a very confined

area. This often created tensions and difficulties, which inevitably

got amplified when personal space was almost non-existent. Put simply

some individuals could cope but many others couldn’t. Interestingly

those that rose to the top and excelled were not always the better

educated. It was a unique experience, which was alien to civilian life.

What you learnt early on was that in extreme conditions your life was

likely to depend on your neighbour.

Daily life revolved around the normal routines of eating, sleeping and

personal hygiene. Importantly there was always plenty of food

available. As you could imagine the quality was quite variable but

always adequate for a growing lad.

The short trips of HMS Vanity

meant that there was frequent opportunity to eat ashore where the food

was always better. Time may have dimmed the memory but I definitely

remember the food being better in Scotland than down south. Perhaps

things never change.

Sleep was something you grabbed whenever the opportunity arose.

Fortunately I was someone who could sleep standing on my head but not

everyone was as lucky. All the ordinary seamen slept in hammocks, which

is an acquired art which some struggled to come to terms with. The

hammocks were slung in rows across the width of the ship and were

stored away during the day. There was no space between the hammocks so

the experience was like sleeping with three in a bed. As a consequence

there was no privacy and you can imagine the chaos as the duty watches

changed at midnight and again at 4 am. By day, one often found an

opportunity for a catnap normally stretched out on any available bench

or seat.

Washing facilities were very basic. We always had fresh water, as we

were able to replenish the tanks on the ship regularly. Most of our

personal washing was done out of a bucket of water, which included a

full body wash. There was a cold- water shower but it was rarely used

because it wasted water and was difficult to set up. When in Rosyth we

would jump at the opportunity to make the short journey to Dunfermline

where there was a range of bath houses including a Turkish one. I can

remember how wonderful it felt spending an hour wallowing in a deep

bath full of boiling hot water.

At the end of the war in Europe in June 1945, HMS Vanity

was chosen with another destroyer to escort a Royal Navy Cruiser to

take King Haakon back to Norway This was a tremendous privilege. The

cruiser went into Oslo the other destroyer went into Christiansfeld and

the Vanity went into Bergen. We had a tremendous welcome from the Norwegian people and believe it or not by armed German soldiers as well.

HMS Vanity was decommissioned

immediately the European war ended and was sold to be broken up in

1947. I joined the crew of Fighter Director Tender 13 which was

scheduled to see action in the Pacific but the atomic bombs dropped on

Japan brought the war to a close. I spent the last few months in HMS Illustrious before leaving the navy to read Agriculture at Bangor University and returning to civvy street.

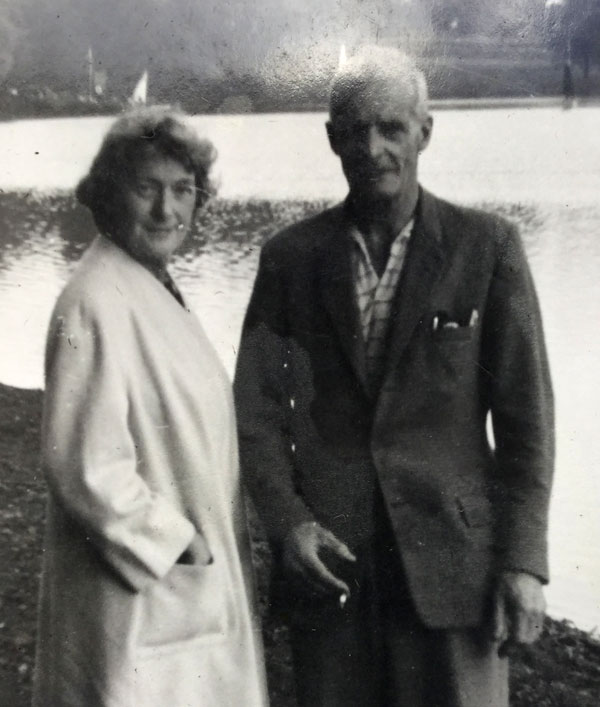

What came next?

Havard was born in Swansea on 25

May 1925 and had matriculated before he left school and joined the Navy

at the tender age of seventeen but he was now twenty plus and, without

a trade or profession, he had a lot of catching up to do. He decided to

study Agriculture and was accepted by Bangor University but the

academic year began in September and he was still in the Navy. He went

to see the CO of HMS Illustrious and

explained the situation and was sent to the Lt(Surg) with a note from

the CO and was signed off sick for three months which enabled him to

enrole at the University in September.

As well as graduating from Bangor with a BSc he met his future wife

there, a lecturer in Zoology. He joined the Ministry of Agriculture's

Grassland Centre but left them for the Fertilisers Division of

ICI, visiting farms in Wales and the border counties. Over time

he took on various management roles, living in different parts of the

UK. He marrried on Anglesy in 1952 and had two children, a boy

and girl. After twenty years with ICI he took early retirement to

avoid having to take an office job in London. He saw this as a change

of direction rather than retirement and bought into an agricultural

merchant in Cheshire and a small farm just across the border in Wales.

When he did finally retire he bought an

apartment in Tatton Hall at Tatton Park near Knutsford, Cheshire. He

greatest pleasure in life latterly was his family. He had five

grandchildren and was lucky enough to meet his great granddaughter

regularly before he died. He was old in years but mentally alert and

active with a mobile phone and an iPad and found out about the link

between Winteringham and HMS Vanity by finding John Kirk's website about the village, Winteringham History and Genealogy, which although no longer updated can be accessed on the British Library's Web Archive.

Friends and family were confident he would

live to be a hundred but he had a heart problem which led to his death

in the Countess of Chester Hospital at Chester on 24 October 1919 aged

94.

The twin 4-inch guns on HMS Vanity escorting an East Coast Convoy

Forward mounting in the raised B position (left) and aft mounting in the raised X position (right)

Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

In

Nelson's time the Navy used spherical solid shot, cannon balls, which

were muzzle loaded after ramming home an explosive charge. Iron clad

warships led to the development of armout piercing shells, which were

breech loaded, but the cordite propellant was packed separately in a

cloth bag and loaded into the breech after the shell, as in the case of

the BL 4.7 inch Mk 1 fitted in some V & W destroyers built at the

end of WW1, such as HMS Venomous.

Their 4.7 inch diameter 50 lb shells made them an effective Anti Tank

Gun at Boulogne in May 1940 but they provided little defence

against attack from the air. The separate ammunition gave them a slow

rate of fire, of 5 to 6 rounds per minute. Other V an Ws such as HMS Vimy

mounted the QF (Quick Firing) Naval Gun Mk V, where the cordite charge

was contained in a brass cartridge case giving a higher rate of fire.

The shell weight was 31 lbs.

From the 1930s onwards many of the V &

Ws had these guns replaced by twin QF 4 inch Naval guns Mk XVI, with

fixed ammunition, where the shell was mounted in the mouth of the brass

cartridge case, which was fired electrically, giving a rate of fire of

up to ten rounds per gun. They were HA (High Angle), DP (Dual Purpose)

guns suitable for engaging surface and land or aircraft targets, They

could fire either 35 lb HE shells against aircraft, or 38 lb Semi

Armour Piercing shells at surface and land targets. Against aircraft

the shell would have a time fuze , and for other targets the fuze would

be impact.

They are usually referred to as WAIR

Conversions, and were conceived as advance models of the Hunt Class

Escort Destroyers, intended for escorting the vulnerable East Coast

convoys (see V & W Class Destroyers, 1917-1945; by Antony Preston pge 57). The rounds were raised by a lift on a

"cruet" from the magazine and the mounting could fire 15 - 20 rounds per minute.

Each Gun Crew consisted of fourteen men, each with his own specific job

to do. Frank Donald, a retired Lt Cdr in the Royal Navy who served in

HMS VIgilant in 196? which

was fitted with identical guns to those shown in these two photographs

explains below the role of each man in the Gun Crew.

The crew of the twin mounting would be:

Officer of the Quarters – In general charge of the mounting and crew

Layer – Captain of the mounting

Seated inside the shield on the right of the mounting

Responsible for elevating the mounting and aiming it in elevation when in local control

Equipped with sighting telescope for surface firing, and open “cartwheel” sight for anti-aircraft firing.

Trainer – Seated inside the shield on the left of the mounting

Responsible for training the mounting and aiming it in bearing when in local control

Equipped with sighting telescope and “Cartwheel sight”

2 Breechworkers

Standing on a step outboard of the breech of each gun

Responsible for opening and closing the breech, and opening and closing the Firing Circuits by means of the Interceptor Switch

When

the breech is open the breech block is held down by a spring catch. The

recoil of the gun opens the breech and ejects the spent cartridge.

2 Loaders

Standing in rear of each breech.

Responsible for ramming the round into the breech, using his padded clenched fist.

As the round goes home the catch is released and the breech closes and

the gun fires. The loader clenches his fist to keep his fingers clear.

4 Ammunition Supply Numbers (two each side)

Responsible for taking the rounds from the ready use locker or hoist and handing them to the Loader.

In

anti-aircraft firing the round has to be placed on the Fuze Setting

Machine so that the flight time can be set, before it is handed to the

loader.

2 Fuze Setters, inside the shield, (one each side)

Operates the Fuze Setting Machine to set the flight time, which is received from the Central Transmitting Station.

Communications Number

Mans the telephone to the Director and Transmitting Station

In the left hand photograph a

ready use locker can be seen on each side inside the breakwater. The

mounting is trained straight ahead. The Breechworkers are standing in

place, and the breech blocks are down ready for loading. Two Ammunition

Supply numbers can be seen on each side.

In the right hand photograph

a coastal convoy can be seen astern. The mounting is trained on the

Starboard Quarter at medium elevation. The Officer of the Quarters is

standing on the left. The Breechworkers, Loaders and Ammunition Supply

numbers can be clearly seen. The ready use lockers are forward of

the mounting, between us and the crew.

HMS VANITY

HMS VANITY

These memories of my time as radar operator on HMS Vanity

span the period of two and half years during the last war. 70 years

have elapsed since then and it is poignant to remember that most of the

people I served with and fought are now deceased and importantly their

descendants are no longer enemies but allies and friends.

These memories of my time as radar operator on HMS Vanity

span the period of two and half years during the last war. 70 years

have elapsed since then and it is poignant to remember that most of the

people I served with and fought are now deceased and importantly their

descendants are no longer enemies but allies and friends.