The sinking of the SS Slamat, HMS Diamond and HMS Wryneck - on 27th April 1941

during the evacuation of troops from Greece

The

Italian invasion in October 1940, usually known as the Greco-Italian

War, was followed by the German invasion in April 1941. German landings

on the island of Crete (May 1941) came after Allied forces had been

defeated in mainland Greece. The most authorative and detailed account

of the evacuation of the troops from Greece was published in Supplement 38293 to The London Gazette on Tuesday 18 May 1948.

It contains the official accounts of the senior officers responsible

for directing the operation to take allied troops to Greece (Operation Lustre) and Operation Demon to evacuate them after the fall of Greece to German forces, It has been saved as a PDF so that it can

be read online on this website. Although a great tragedy the loss of

HMS Wryneck was only a small part of this operation which successfully evacuated 50,000 troops.

The

Italian invasion in October 1940, usually known as the Greco-Italian

War, was followed by the German invasion in April 1941. German landings

on the island of Crete (May 1941) came after Allied forces had been

defeated in mainland Greece. The most authorative and detailed account

of the evacuation of the troops from Greece was published in Supplement 38293 to The London Gazette on Tuesday 18 May 1948.

It contains the official accounts of the senior officers responsible

for directing the operation to take allied troops to Greece (Operation Lustre) and Operation Demon to evacuate them after the fall of Greece to German forces, It has been saved as a PDF so that it can

be read online on this website. Although a great tragedy the loss of

HMS Wryneck was only a small part of this operation which successfully evacuated 50,000 troops.

The SS Slamat was

a twin-prop ship of 11,636 tons of the Rotterdamsche Lloyd (RL). The

vessel was launched in 1924 by shipyard De Schelde in Flushing carrying

passengers between Rotterdam and the Dutch Dutch East Indies. In order

to compete with faster newer ships Slamat

was modernized in 1931. Her length was increased to

155.5 meters by altering the bow which enabled the De Schelde

steam turbines to increase the ship's speed from 15 to 17 knots. The Slamat was in Batavia, capital of the Dutch East Indies, when Germany invaded

the Netherlands in May 1940. She

was chartered by the British

Ministry of War Transport and converted into a troop-ship (on left) in Sydney,

Australia. She was mainly

deployed in the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean carrying

British Empire troops to Egypt until the Italian invasion of

Greece in October 1940.

The sinking of the SS Slamat is described as "the greatest disaster in Dutch Merchant Navy History" on the website of the Museum of her shipowner Rotterdamsche Lloyd (RL). The part played by the Dutch Liner Slamat in the evacuation and the rescue of survivors from the Slamat by Wryneck and Diamond and the sinking of all three ships is described below.

***********

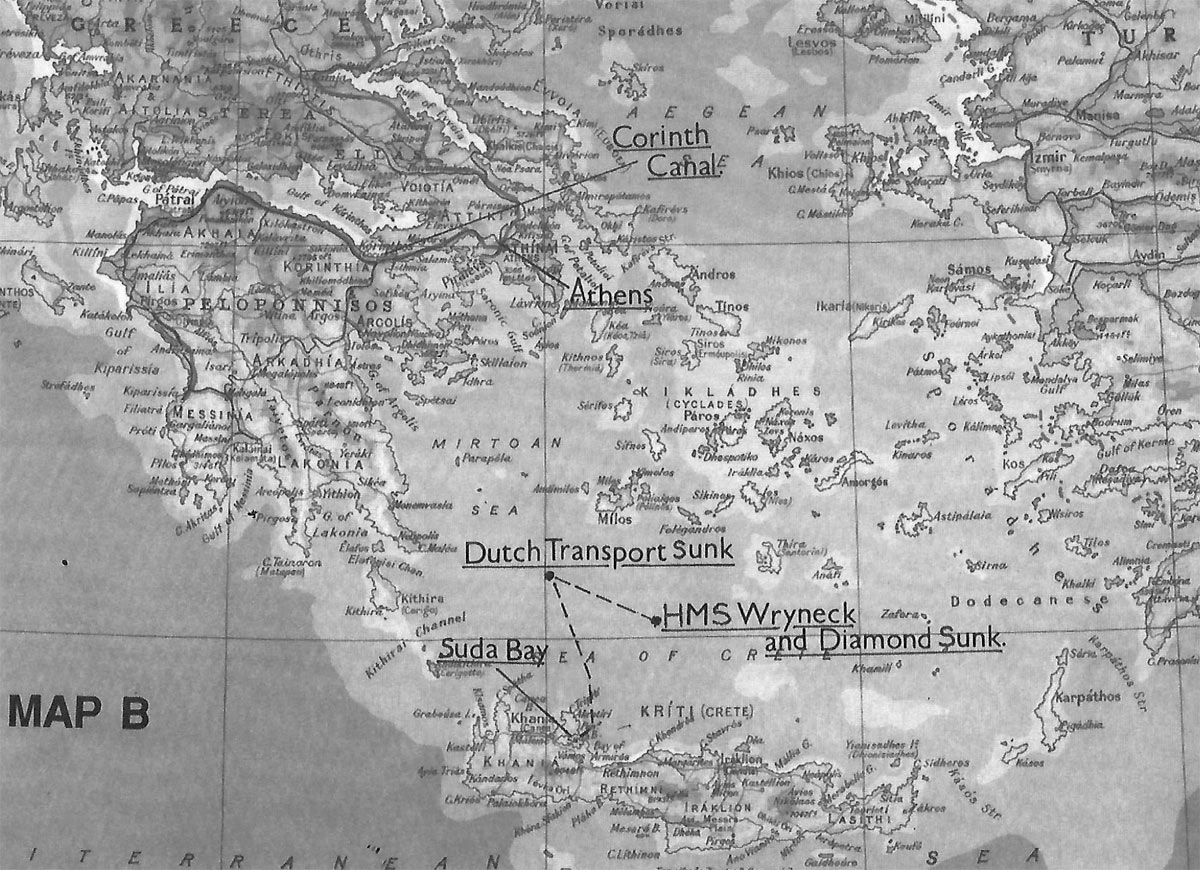

In the afternoon of 26 April, 1941,

Slamat, HMS

Glenearn and

Khedive Ismail of 7,290 ton (under Egyptian flag) escorted by the cruiser HMS

Calcutta and five destroyers were directed from Crete to evacuate the troops from Nauplia in the in the Peloponnese. The

Glenearn,

an LSI (Landing Ship Infantry), was bombed and a bomb hit the engine room stopping the LSI dead in the water. The destroyer HMS

Griffin was ordered to tow the landing ship back to Crete. The loss of the

Glenearn

was a bitter set back; their landing craft would have madeb the evacuation of the troops much easier.

In the evening the ships dropped anchor in the bay at Nauplia. The harbour was still blocked by the wreck of the Ulster Prince

and since the landing craft of the Glenearn were not available the troops could only be ferried to the ships in the

life-boats of the ships themselves and some small loocal boats. The

cruisers HMS Orion and HMS Perth and the destroyer HMS Stuart which had replaced HMS Glenearn, took the first 2,500 troops aboard. By 03.00 the Khedive Ismail had taken aboard no troops at all and Slamat only a few hundred, when HMS Calcutta signalled that departure was due. Captain T. Luidinga of the Slamat knew that hundreds of evacuees remained on shore and against orders he continued to embark troops. HMS Calcutta and the Egyptian ship only departed at 04:00 and Slamat

at 04:15. In spite of the decision by captain Luidinga to

board more troops there were only 600 troops onboard, only half of her capacity.

After a few hours they were attacked in the Sea of Pelagos by nine German Ju 88 bombers and the

Slamat (on left)

received

a direct hit between the bridge and the foremost chimney which

caused a fierce blaze. The crew tried to control the fire but this was

made more difficult by heavy machine gun strafing by

Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter airplanes and Ju 87 (Stuka) bombers. The

ship received another near-miss and started to list.

Captain Luidinga ordered abandon-ship. The life boats and

rafts which had been left were inadequate and

two overcrowded life-boats capsized. To make things worse

the drowning troops were machine gunned in the water by the German

planes while the other ships maintained heading and speed. HMS

Calcutta took a few survivors aboard and ordered the destroyer HMS

Diamond to stay and rescue as many survivors as possible.

HMS

Wryneck and two V & W destroyers in the Australian Navy, HMAS

Vendetta and HMAS

Waterhen, were ordered from Souda Bay in Crete to reinforce the escort for the Convoy. HMS

Wryneck was ordered to assist HMS

Diamond in rescuing survivors from the

Slamat. After rescuing as many men as possible HMS

Wryneck fired a torpedo at the

Slamat which sank her within minutes. HMS

Diamond already had about 600 victims onboard and HMS

Wryneck

another few dozen and at 13:00 headed for Crete. A

quarter of an hour later both ships were attacked by Ju87 dive

bombers coming out of the sun. HMS

Diamond received two hits and sank within eight minutes. HMS

Wryneck received three hits, capsized on her port side and sank within fifteen minutes. The crew of the

Wryneck

had been able to lower a single life-boat and both destroyers had

launched their three Carley rafts. The capacity of these was far short of what was needed and hundreds drowned,

especially those wounded.

This is an extract from p3053 of the Supplement to the London Gazette referred to above.

Loss of Diamond and Wryneck

When it was realised that Diamond had not arrived with Phoebe and other destroyers I became anscious about her. From 1922 to 1955 Diamond had been called without reply. As Diamond had last been heard of with Wryneck during the forenoon, Phoebe and Calcutta were asked whether Wryneck hd been seen going away with GA.14 since I did not wish to ask Wryneck herself to break to break W/T silence. Their replies at 2235 and 2245 gave no definite indication. I therefor despatched Griffin to the position of the sinking of the Slamat to investigate. At 0230 Griffin rerported that she had come upon a raft from Wryneck and everything pointed to the fact that both Wryneck and Diamond were sunk. HMS Griffin picked up about 50 survivors. Wryneck's

whaler was reported to have made towards Cape Malea. This eventually

arrived at Suda. The total naval survivors from the two ships

comprised one officer and 41 ratings. There were, in addition, about 8

soldiers. From statements of the survivors, it appears tht the two

ships were bombed at about 1315 both receiving hits which caused them

to sink almost immediately.

In the evening of 27 April the destroyer HMS

Griffin was sent out to establish why HMS

Diamond and HMS

Wryneck had failed to return.

Griffin found two rafts at the spot where

Slamat had sunk. Fourteen survivors were picked up and next morning another four, who were taken to Crete. The life-boat of HMS

Wryneck

reached a little rocky island thirteen miles south east of Milos on

the 28th of April. Here they found a Greek fishing boat full up with

Greek and British refugees from Piraeus. That evening the

fishing boat and the life-boat sailed for Crete and were spotted during

the night by a landing craft on its way with refugees from Port

Raphtis. All the evacuees were taken aboard the landing craft and

arrived safely at Crete.

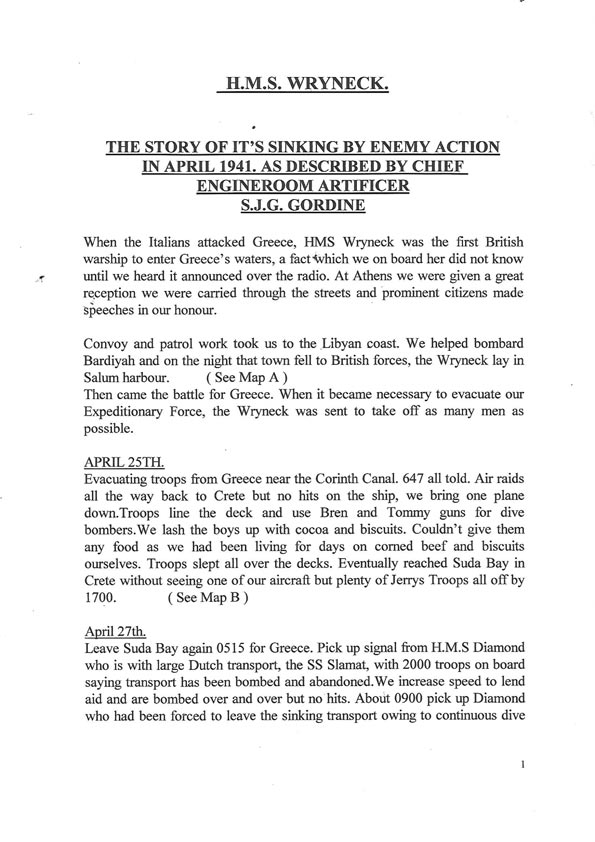

The Sinking of HMS Wryneck

The men who died

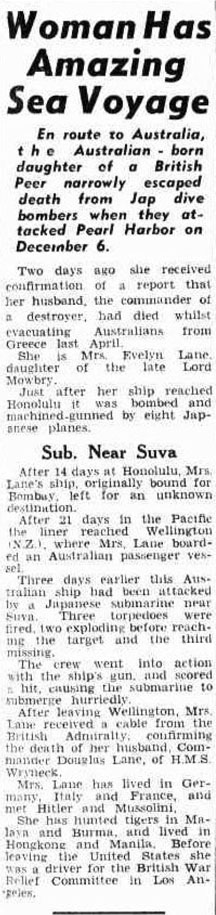

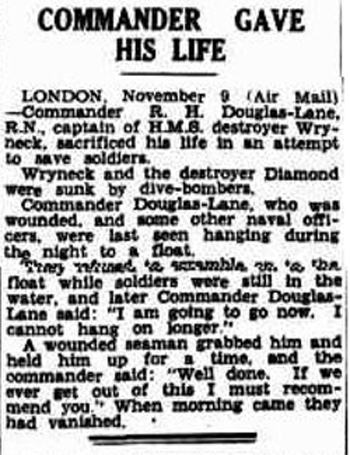

Cdr Douglas-Lane was appointed CO of HMS Wryneck on 26 July 1940 during her refit in Malta Dockyard, a month before she was placed in Commission on 29 August, The Admiralty records of her activities between then and her loss can be seen on U-Boat.net

On the 25 April HMS Wryneck was

ordered to Greece to evacuate the Australian 6th Division Signals from

Megara near Pireus, the main port for Athens, east of the entrance to

the Corinth Canal. She replaced HMS Pennland, a former Atlantic passenger liner requisitioned by the Ministry of War Transport (MOWT) and converted into a troop carrier, bombed and sunk the previous night.

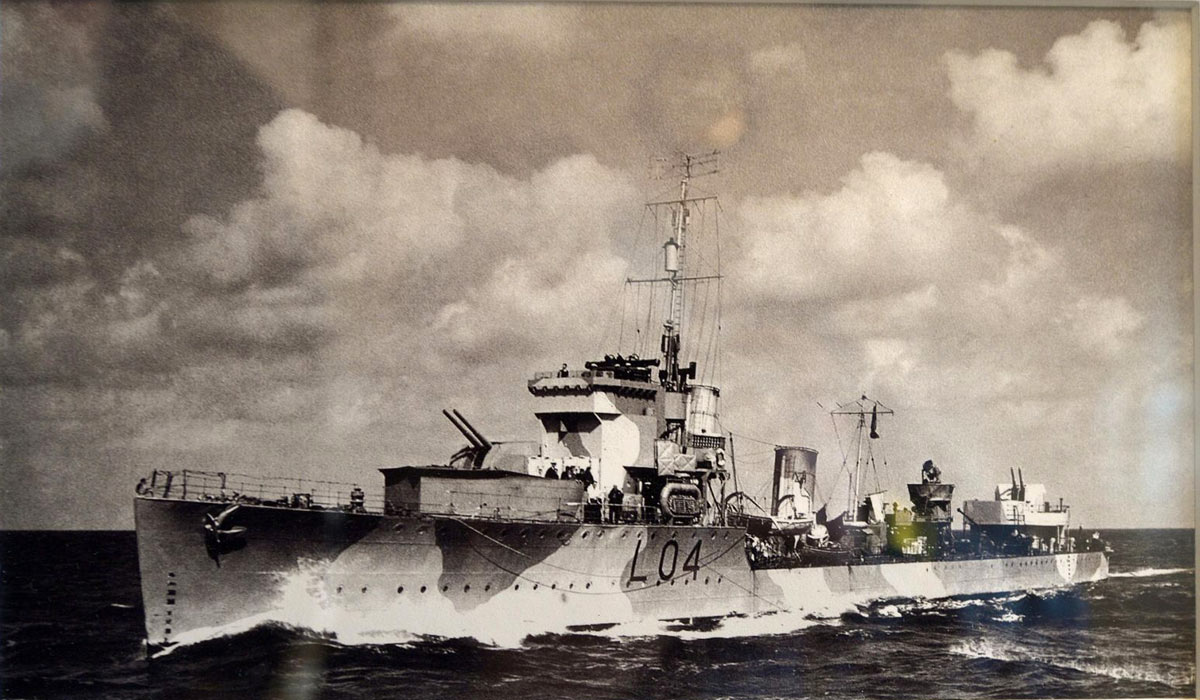

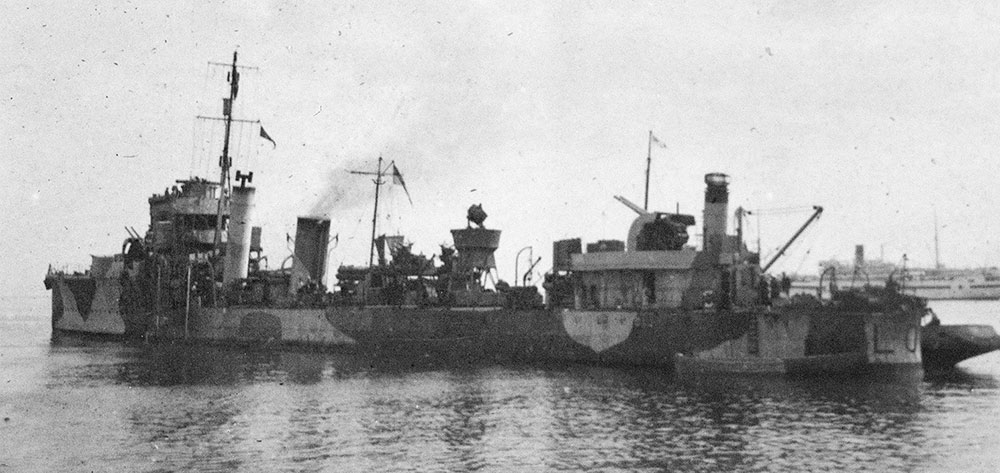

These two photographs from the Australian War Memorial website show the

647 troops of the Australian Signals Division crowding the deck of Wryneck

(left) and gratefully accepting loaves of bread handed to them by the

crew of an oil tanker (on right), the first bread that the men had

eaten for three

weeks. ERA Stanley Gordine began his Diary on this day and noted

"Troops

line the deck and use Bren and Tommy guns for dive bombers. We lash the

boys up with cocoa and biscuits. Couldn't give them any food as

we had been living for days on corned beef and biscuits. Troops slept

all over the decks. Eventually reached Suda Bay in Crete without

seeing one of our aircraft but plenty of Jerrys. Troops all off by by

1700."

Wryneck was sunk two days later.

The names and fates of all the men in Wryneck when she sunk are recorded on the list of crew members compiled by Ian McLeod

from official records in The National Archives, Kew, and by Brian

Crabb for his book on Operation Demon,

the evacuation of troops from

Greece. Amongst the men who died were the Commanding Officer, Lt Cdr

Robert Henry Douglas Lane RN, and five of his officers. John Reginald

Batt CM/X 53459, Leading Supply Assistant, was one of the hundred

ratings who were killed. His story is told below by his his great

nephew, Andrew Lyle, in Australia.

Lt Cdr Robert Henry Douglas Lane RN

Robert Henry Douglas Lane was born

on 15 February 1896, the son of “Charles M.R. Douglas Lane Esq,

Gentleman” (the entry on his Service Certificate) and joined the Navy

on 10 January 1909 when he was thirteen. His hand written service

certificate is difficult to read and to interpret but after gaining one

months seniority on passing out from Dartmouth Naval College he was

appointed Midshipman on 15 September 1913 and on the outbreak of

hostilities in August 1914 was serving in the battleship HMS Africa. Two years later to the day he was promoted to Acting Sub Lieutenant and on 15 November 1915 joined HMS Hindustan

in the 3rd Battle Squadron. By the 15 October 1917 he was a full

Lieutenant and he completed his wartime service in destroyers, the Nonpareil and the Patriot, latterly as a “Jimmy the One", First Lieutenant.

On 15 July 1919 he was appointed 1st Lt of a former yacht and despatch vessel launched as Margarita in 1900, renamed Semiramis in 1910 and Mlada in 1913 which was requisitioned by the Admiralty in 1918 and commissioned as HMS Alacrity in 1919. HMS Alacrity had been requisitioned for use as an Admiral's yacht by the Commander-in-Chief of the China Station. This

was his introduction to the complex problems faced by the Navy in

protecting British interests on the China Station. Britain was the

first of many foreign powers to take advantage of Chinese weakness to

secure rights to trade and settle in treaty ports, concessions and

enclaves along the coast of China and major rivers. The process began

with the ceding of Hong Kong to Britain at the end of the First Opium War (1841-2) and

accelerated with the fall of the Quing dynasty and the establishment of

the Republic of China in 1912. By 1920 there were 60,000

foreigners living in the International Settlement at Shanghai, China's

largest city on the delta of the four thousand mile Yangtze River which

flowed from west to east separating north from south China. Russia, France, Germany and Japan also acquired treaty ports from the weak government and had warships on the China coast and along the Yangzte to protect their ports and citizens. He only served in Alacrity from 15 July 1919 to March 1921 but at present nothing further is known of his role in Alacrity. He returned to Britain in the troop carier SS Devanha in June 1921.

On joining Alacrity he expressed an interest in an “appointment to destroyers” and on his return to HMS Pembroke, the shore base at Chatham on the Medway, he was sent on the Gunnery Control Course (GCC) and the Short Torpedo Control Course (TCC) and served in the V & W Class destroyer HMS Viscount from 15 Dec 1921 to 28 November 1923. He was promoted to Lt Cdr in October 1925 and in October 1927 passed the examination for command of a destroyer and from 9 April 1928 – 6 May 1930 was CO of HMS Whitehall. He transferred to HMS Seraph on 6 June 1930 and joined HMS Diamond on 30 March 1932 while under construction and for her sea trials. At the outbreak of

hostilities in 1939 he was back on the China Station at HMS Tamar as Naval

Provost Marshal in Hong Kong. There is no obvious explanation for him being

appointed to this senior post ashore in the Regulating Branch of the

Navy. Was it related to his marriage to the daughter of Lord Mowbry?

He returned to the Britain in early 1940 and was given command of the ancient freighter SS Moyle, one of three blockships ordered to Dunkirk on the last night of the evacuation on 3-4 June 1940.

Lane and his crew rammed her into the west pier and scuttled her, prior

to becoming among the very last to be evacuated from the battered port.

He was subsequently among those men mentioned in despatches in The London Gazette

of 10 October 1940, for "good services when carrying out blocking

operations in enemy occupied ports". He was also MID for service in

Norway but at present nothing is known about what he did to merit this.

Lt Cdr Douglas-Lane was appointed CO of HMS Wryneck on 26 July 1940 while she was undergoing a refit in Malta Dockyard. She was placed in Commission on 29 August and served

with distinction in the Mediterranean, and more particularly

during the evacuation of Greece. Although Douglas-Lane (his name is

often hyphenated) was "Placed on retired list (age) with rank of

Commander 15 February 1941" he remained in command and two months

later was killed with five of his officers and one hundred of his men. Having

assisted in the withdrawal of troops from Megara on 25 April 1941, and

in rescuing survivors from the lighter A. 19, Lane was ordered to take

the Wryneck on a similar mission two nights later. HMS Wryneck and her

consorts departed Navplion too late to avoid enemy attention

in the first hours of daylight and at 7 am thirty enemy dive bombers

commenced a devastating attack on the Wryneck, the Diamond and the Dutch Slamat.

This description is taken from the catalogue entry for the sale of Lane's medals in 2002:

‘Wryneck, meanwhile, had been equally unfortunate. Taken unawares in the same way as Diamond,

a bomb had struck the foc’s’le near ‘A’ gun, killing or wounding

everyone at the gun, on the bridge and in the sick bay, shattering the

stokers’ mess deck and killing numbers of stokers and soldiers. Another

fell down the engine room hatch bursting all the steam pipes, and a

third bomb struck aft setting an ammunition locker on fire. With the

ship moving at about 18 knots, with a heavy growing list to port, an

E.R.A. managed to open the safety valves; then, with others, he got a

whaler away which was practically undamaged, and released the rafts

before abandoning ship ...’

The ERA Paul Gordine -

"...

never thought the ship would sink ... I put the heavy list down to the

the fact the skipper was making a heavy turn. I think that everyone

thought the same until it was too late, hence the heavy death

toll; no orders were given to abandon ship, it was when I looked

up at the bridge in the hope of seeing somebody doing something when I

saw a heap of torn papers come blowing down, that I thought it must be

serious because they are destroying confidential papers."

There

were a number of rafts and Carley floats drifting in a growing patch of

oil, and a few carried survivors. Commander Lane of the Wryneck, with two of his RNVR Sub. Lieutenants, Jackson and Griffiths, and his Midshipman Peck were on one of them.

Able Seaman Taylor helped to haul them on to the raft. They were all

badly wounded and coated in oil. For a little while they clung to the

raft as it rolled in the rising sea until they slipped off, too weak to

hold on any longer ...

When a handful of Wryneck’s men were eventually picked up, the senior surviving rating was asked to complete a report. He ended:

"The men of the Wryneck wish me to add that we have lost a fine ship, fine officers and a magnificent Captain."

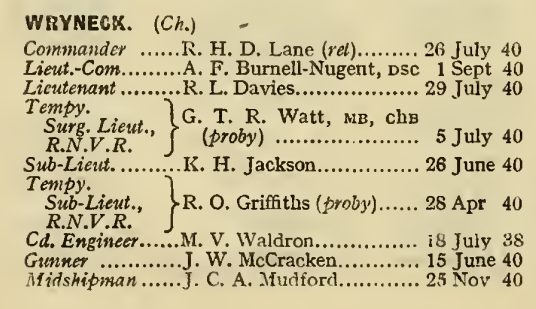

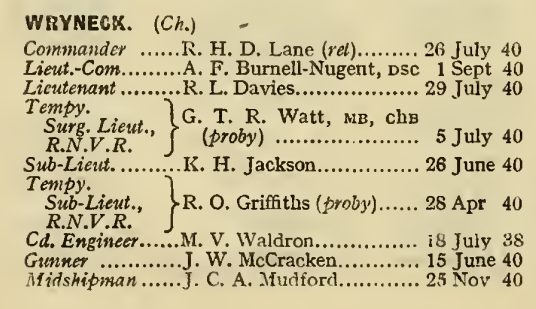

Officers in the Navy List for April 1941

The Navy List is not always accurate

The Navy List is not always accurate

Lt Cdr Burnell-Nugent left HMS Wryneck in Jan 1941 and was in HMS Jersey when she sank on 2 May 1941

Mid Basil Peck is thought to have replaced Mudford before Wryneck was sunk

Cdr Robert Henry Douglas Lane RN and John Reginald Batt (CM/X 53459) were two of the men who died

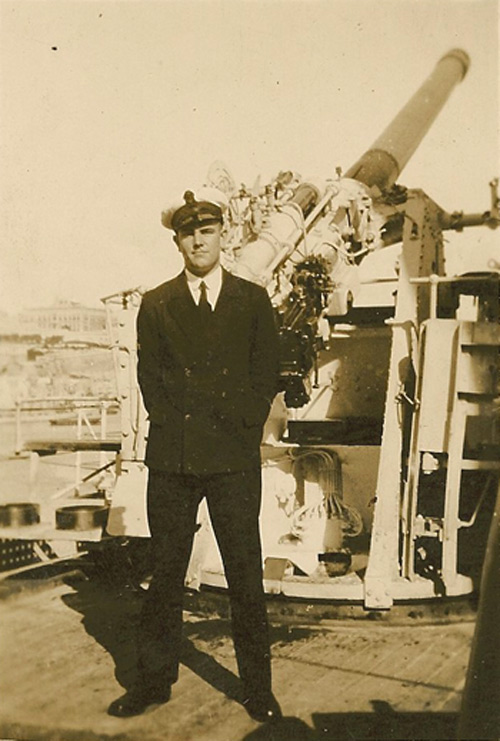

John Reginald Batt CM/X 53459

Leading Supply Assistant

John Batt was was born on the 16th

May 1918 in Sandgate Kent to Walter Leonard Batt and Emily Elizabeth

Batt. He came from a naval family and was educated at the Royal Hospital School

which was founded at Greenwich in 1712 to provide an education for

children from a naval background. It occupied the present buildings of

the National Maritime Museum until 1933 when it moved to the village of

Holbrook in Suffolk on the bank of the River Stour near HMS Ganges, the boys training school on the Shotley peninsula.John Batt joined the Navy before the war, was not married and left no

children when he died. Only 27 crew members survived the sinking of HMS

Wryneck. His body was not recovered and he appears on official lists as MPK (Missing Presumed Killed). The photograph of him posing in front of one of the 4-inch HA / DP main guns in Wryneck (above right) was provided by his great nephew, Andrew Lyle, in Australia. Andrew is building a scale model of HMS Wryneck as a memorial to his uncle and all the men who died when she sunk on 27 April 1941

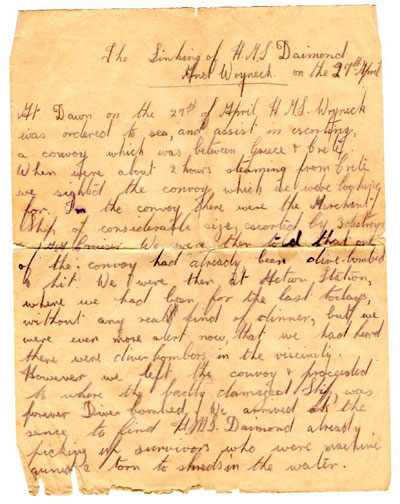

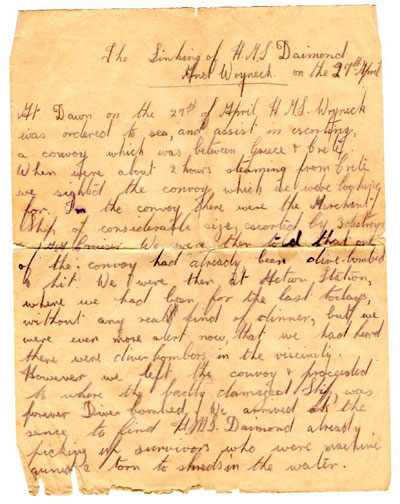

"We have recently

found in a relative's possessions a 7 page hand written letter with

detailed drawn map (but see below) from a sailor on HMS Wryneck

detailing how they were ordered to assist picking up of survivors

from a sinking ship, states how on arrival HMS Diamond

was already there, and describes how after picking up survivors

they were attacked by Junkers 87 dive-bombers. He describes jumping

overboard , the sinking of both destroyers, and how he was picked up

and survived but never wanted to go to sea again."

"At dawn on the 27th of April HMS

Wryneck

was ordered to sea, and assist in escorting a convoy which was between

Greece & Crete. When we were about 2 hours steaming from Crete we

sighted the convoy which we were looking for. In the convoy there were

the Merchant ship of considerable size, escorted by 3 destroyers &

HM Cruiser. We were then told that one of the convoy had already been

dive-bombed & hit. We were then at action station, where we had

been for the last to days, without any real kind of dinner, but we were

even more alert now, that we had heard there were dive bombers in the

vicinity. However left the convoy & proceeded to where the badly

damaged Ship, was forever dive bombed. We arrived at the scene to find

H.M.S Diamond already picking up survivors who were machine-gunned

& torn to shreds in the water.

However, we picked up as many as we could, and then a few of them were

already half dead. When we finally satisfied ourselves that there was

nothing more to be done, we made up our minds to return to Crete. That

was about 12.15, so we put ourselves or rather took up our positions.

Diamond then flashed that they were going to torpedo the already badly blazing ship. The

Diamond fired

one only which hit right amid-ships. We saw the vessel give a great

lurch and then begin to sink very quickly. During these operation

Dive-Bombers never came near us. Then when they began to think they

were saved & all was well, out of nowhere came those Junkers 87,

those terrifying dive bombers, with something like vengeance, which

they quickly got. All we knew was when we heard the whining of the

machine & the machine guns & a second later bombs.

I never experienced as much in all the war as I did those next five

minutes. One bomb landed on the forward gun & wiped out nearly

everyone out, then one landed on the after gun but lucky only one was

hurt, the other one or two were near misses, but they did all the

damage. After the Nazis thought they had done a good job which they

nearly had, they never bothered us again, which was to my relief. I

didn’t fancy having a machine gun bullet in me. However the ship now

had a great list to port & was sinking rapidly. My Pal who I owe my

life to found me forward in the (galley flat) and these were the words

he spoke to me quite calmly. They got us, Dolly. Dolly was my nick

name in case you want to know. We went out on the Upper Deck together,

& he said to me, Have you got a life belt,

I said no, I didn’t need one, but he gave me one as he had two and we

did a bit of work together, we untied a Carley Raft & threw it over

the side, however the ship was going about 20 knots & we could not

hold on to it, that we made our objective. We travelled a bit further

on, I should say a few seconds, because all this happened within six

minutes. I look over to have a look at the

Diamond

but it had already gone down. When we finally decided to jump over, me

& my pal, we gripped one oar each, before we went. Believe me they

came in handy. We made to get clear of the oil-fuel which was now

spreading on the water, and then for the rafts which we could not see.

When we had swam a couple of miles together, we noticed that someone

else had got the whaler free so we made for this, eventually I think we

swam about 3 miles before we caught up with the whaler, which we then

noticed had collected two rafts, We got to one of these rafts and

clambered inboard.

The time would then be about 2.15 - 2.30. We kept good hearts and I

joked with a few of my favourite comrades who were in the whaler. I

cannot tell you every little detail, but I’m writing this down to give

an idea what I thought was a terrible ordeal.

It came to dusk & I think we had picked only two more survivors up,

then a rough sea sprang up, as I have already told before we were on a

raft. However it began to get rougher & rougher every minute. The

whaler who was towing us suddenly decided to cut us adrift. We never

thought such a thing could happen among English sailors or more so one

that you share the same ship & eat with. However when we found to

our misfortune that we were actually adrift, we almost gave up. Time

wore on hour after hour went by till we thought that we would never be

picked up when suddenly about half past three in the morning we sighted

a ship but not before they had sighted us, it was a destroyer, one of

those dark grey shapes. We realised but it took quite a bit to do so

that it was making straight toward us, at least that what we thought,

but thank goodness we were wrong. I’ll never forget that night of

terror.

The destroyer finally came along-side us with great skill, and we were

pulled up the side of the ship, our legs were numb & we could

hardly use them, but we were full of smiles. We were treated splendidly

aboard HMS

Griffin which was

the name of the destroyer. I was only interested about getting

something to eat. I didn’t. We got something to drink which did

us the world of good. When we arrived at Crete the same morning I was

relieved & never wanted to go to sea again. But I'll never forget

the splendid behaviour of my ship company."

“It was a scene of total carnage and

devastation. The deck of the ship and the water surrounding was covered

in debris. I managed to find a rope and abseiled down the ship where I

dived into the water. I don’t know if it was bomb shock or just his

sense of humour but in the middle of all this death and destruction a

sailor was clinging to the top of a floating barrel merrily singing

‘roll out the barrel.’ It was quite a surreal moment.”

"I opened my eyes and saw utter

carnage. There were bodies everywhere. I realised I was the only guy in

the mess moving. The ship started to list heavily to one side and

started to sink. I knew I had to get out as quickly as possible.”

HMS WRYNECK

HMS WRYNECK

The

Italian invasion in October 1940, usually known as the Greco-Italian

War, was followed by the German invasion in April 1941. German landings

on the island of Crete (May 1941) came after Allied forces had been

defeated in mainland Greece. The most authorative and detailed account

of the evacuation of the troops from Greece was published in Supplement 38293 to The London Gazette on Tuesday 18 May 1948.

It contains the official accounts of the senior officers responsible

for directing the operation to take allied troops to Greece (Operation Lustre) and Operation Demon to evacuate them after the fall of Greece to German forces, It has been saved as a PDF so that it can

be read online on this website. Although a great tragedy the loss of

HMS Wryneck was only a small part of this operation which successfully evacuated 50,000 troops.

The

Italian invasion in October 1940, usually known as the Greco-Italian

War, was followed by the German invasion in April 1941. German landings

on the island of Crete (May 1941) came after Allied forces had been

defeated in mainland Greece. The most authorative and detailed account

of the evacuation of the troops from Greece was published in Supplement 38293 to The London Gazette on Tuesday 18 May 1948.

It contains the official accounts of the senior officers responsible

for directing the operation to take allied troops to Greece (Operation Lustre) and Operation Demon to evacuate them after the fall of Greece to German forces, It has been saved as a PDF so that it can

be read online on this website. Although a great tragedy the loss of

HMS Wryneck was only a small part of this operation which successfully evacuated 50,000 troops.

"At dawn on the 27th of April HMS Wryneck

was ordered to sea, and assist in escorting a convoy which was between

Greece & Crete. When we were about 2 hours steaming from Crete we

sighted the convoy which we were looking for. In the convoy there were

the Merchant ship of considerable size, escorted by 3 destroyers &

HM Cruiser. We were then told that one of the convoy had already been

dive-bombed & hit. We were then at action station, where we had

been for the last to days, without any real kind of dinner, but we were

even more alert now, that we had heard there were dive bombers in the

vicinity. However left the convoy & proceeded to where the badly

damaged Ship, was forever dive bombed. We arrived at the scene to find

H.M.S Diamond already picking up survivors who were machine-gunned

& torn to shreds in the water.

"At dawn on the 27th of April HMS Wryneck

was ordered to sea, and assist in escorting a convoy which was between

Greece & Crete. When we were about 2 hours steaming from Crete we

sighted the convoy which we were looking for. In the convoy there were

the Merchant ship of considerable size, escorted by 3 destroyers &

HM Cruiser. We were then told that one of the convoy had already been

dive-bombed & hit. We were then at action station, where we had

been for the last to days, without any real kind of dinner, but we were

even more alert now, that we had heard there were dive bombers in the

vicinity. However left the convoy & proceeded to where the badly

damaged Ship, was forever dive bombed. We arrived at the scene to find

H.M.S Diamond already picking up survivors who were machine-gunned

& torn to shreds in the water.

George

Dexter still shakes his head in disbelief when he remembers the day he

survived TWO ship sinkings by the German Luftwaffe. George, who is 96,

is the only known living survivor of the Luftwaffe’s attack on

evacuating Allied ships SS Slamat and HS Diamond,

on April 27 1941, in the Greek Mediterranean during the Second World

War. He was one of just eight soldiers, one naval officer and 41 seamen

to survive the disaster. The other 843 men perished in the attacks.

George

Dexter still shakes his head in disbelief when he remembers the day he

survived TWO ship sinkings by the German Luftwaffe. George, who is 96,

is the only known living survivor of the Luftwaffe’s attack on

evacuating Allied ships SS Slamat and HS Diamond,

on April 27 1941, in the Greek Mediterranean during the Second World

War. He was one of just eight soldiers, one naval officer and 41 seamen

to survive the disaster. The other 843 men perished in the attacks.