Lt George C Crowley was appointed as CO of HMS Walpole in September 1943. He had joined the Navy as a 17 year old cadet in 1933 and this was his first command and although Walpole

was an old ship he was very proud of her. In the 1970s, after his

retirement as Rear Admiral George C Crowley DSC and bar, he wrote an

unpublished account of his life at sea. I traced his two sons, Patrick and Roger Crowley, and they sent me a copy

of the chapter dealing with his time as CO of HMS Walpole and scans of wartime photographs from his album.

This extract from ‘A Naval Career’ by George Crowley describes his time as CO of HMS Walpole

It begins with his return from Australia where he had been on loan to the Royal Australian Navy since 20 May 1941

"After an uneventful voyage back home, I was given command of HMS Walpole,

my first real command. Though I had spent six years in small ships, my

experience of handling destroyers was very limited. I was allowed to

berth HMAS Nestor once at

Gibraltar but no matter how much you have been instructed, first-hand

experience is what is really needed. I joined HMS Walpole

at Harwich towards the end of October 1943. She was a first world war

destroyer of the V and W class and so was getting rather long in the

tooth. She was a member of the 16th Destroyer Flotilla and was employed

basically on anti E-boat work, and as an escort for the many convoys of

merchant ships which ploughed south full and returned north largely

empty. We had a crew of 10 officers made up as follows: myself as

captain, a first lieutenant as second-in-command who was an RNVR

officer, a chief engineer who was a commissioned warrant officer, a

warrant office gunner, a lieutenant RNVR, four sub-lieutenants (some

RNVR), and a surgeon Lieutenant. We came at first under a commander (D)

but later on he was relieved by a captain (D) in the leader destroyer.

Front Row: Gunner

(T) C.R. Southgate, Lt A.C. Kingdon, Lt Cdr G.C. Crowley. Lt (E) H.

Caullthard, Sub Lt D.D. Stewart, Sub Lt A.W. Stocker RNVR

Front Row: Gunner

(T) C.R. Southgate, Lt A.C. Kingdon, Lt Cdr G.C. Crowley. Lt (E) H.

Caullthard, Sub Lt D.D. Stewart, Sub Lt A.W. Stocker RNVR

Back Row: Lt Charles Edward Tooley RNVR, Surg Lt William David Troup RNVR, Sub Lt F.O. Farwell RNVR, Sub Lt B.C. Sellars RNVR

Courtesy of Patrick and Roger Crowley

Patroling the Channel and East Coast

The plan was roughly as follows – the sea running from Rosyth to

Southend and on to Portsmouth was largely buoyed and swept by

minesweepers. It was also divided into patrol areas. Ships of our

Flotilla and those of the 21st Flotilla, based at Sheerness, were

detailed for these patrols. Usually we had to be on station by dusk.

Patrols depended to some extent on the weather and there were many

occasions when one was resting quietly and I suppose hoping for a quiet

night, when out of the blue came a signal ordering you on patrol at

once, and then you had to weigh anchor and take up your position at

once. The swept channels were marked by buoys which were generally very

dimly lit. One must have no illusions about the navigational and

pilotage risks, which were considerable. The tides and currents were

substantial and the weather very variable, sometimes foggy, often rough

and sometimes teeming with rain. Furthermore we were on night patrol so

the officer-of-the-watch and his ”winger” had to be ready for immediate

action. Because we tended to be basically night birds, I used to have

the armament manned on a two-watch basis at night, and four-watch basis

when at sea by day. In the event of an alarm or the suspicion of an

approaching E boat the officer-of-the-watch immediately pressed the

“action stations” bell and the whole ship turned to at the double.

Two

things were essential. The first was that all the officers knew exactly

what their duty was, and secondly, that they did not take over until

their eyes were acclimatised to the darkness. People sometimes ask how

much you can see in the dark. The answer is more than you think. If

your eyes are accustomed to the dark, and you have your binoculars

focussed to the grading, it is possible on many nights to see quite a

lot. All the destroyers were fitted with asdic, and one must have no

illusions, because even if E boats came over fairly slowly, a listening

watch would invariably give you a warning. When I took over the

“wallop”, as she was affectionally known, we had a sort of bedstead

radar aerial which gave one a sort of reasonable cover over an area of

about 140 degrees, that is to say about 70 degrees on each bow. In

addition to this we had what we called a “headache” chap. He would be

tuned into the wavelengths usually used by the E boats, and though they

did not always have anything useful to report, there were certainly

occasions when they were invaluable.

From left: Lt C.E. Tooley RNVR, Lt Cdr G.C. Crowley "wearing a funny little anorak thing" and "Simmons" on the bridge of HMS Walpole

Courtesy of Patrick and Roger Crowley

Though I was not experienced at ship handling, I knew all the ropes. I

had some good standing orders which made it crystal clear what the

officers had to do when we were out. One of my main orders was that,

when on patrol and a buoy was missed, I was to be called immediately.

There was one occasion when for some obscure reason I woke up and

decided to go up on the bridge. The First Lieutenant was

officer-of-the-watch and I asked him where we were. It transpired he

had missed a buoy, and was just hoping it would turn up. I immediately

stopped engines and after getting the forecastle party, anchored at

once. Believe this or not, had we gone on another few hundred yards or

so we would have been high and dry on Haisborough Sands. I practically

ate the First Lieutenant for breakfast. It was very interesting that

while a number of destroyers in my group did run aground, some more

seriously than others and even the great (D) got his screws round the

moorings of a buoy, by sheer luck and possibly by being careful, we had

no mishaps - we did however have a few near misses.

The caption in George Crowley's photo album is "Convoying, Winter 1943"

The caption in George Crowley's photo album is "Convoying, Winter 1943"

Courtesy of Patrick and Roger Crowley

There were two main convoys to protect. Those leaving the Rosyth area

were known as the FS when going south, and the FN when going north.

Then there were the Channel convoys that used to run from Southend to

Portsmouth known as CW going west and CE when going east. Usually the

16th Destroyer Flotilla was employed on a patrol but exceptionally we

would have to form part of a close escort of the CE/CW convoys. When

doing the Channel convoys, we used to attend the convoy conference

which was held at the outer end of Southend Pier, which was the longest

pier in Britain. From time to time we used to have a few drinks at the

large hotel which was very near the inner end of the pier. This hotel

had six bars, so they said.

The E-Boat threat

The procedure in the east coast area was for destroyers or frigates on

patrol to drive off E boats which would be endeavouring to destroy

shipping either by torpedo or by laying mines in the most focal areas.

The E boats would normally come over in groups and sometimes they would

encourage the destroyers to give chase, so that another section could

slip past into the searched channel now left empty. As either and FS or

FN convoy arrived so the destroyer on patrol formed part of the escort

of the convoy so long as it was in his patrol area. It would be

mistaken to imagine that the E boat attacks always came from seaward.

Furthermore, they often lay close to a buoy in the hope that their

presence would be missed, at least by radar, and the fact that they

would be stopped would deny detection by the anti-submarine listening

device. It was well to remember that an E boat had effective weapons

and if there were say, a group of three, a destroyer would be unlikely

to be able to take them all on single-handed with any confidence of

success.

During my time in the Walpole

we had many actions against E boats and, although we were fairly

certain we had got some hits, it was not always easy to produce actual

evidence of damage unless of course we actually sank one of the enemy

attackers. Quite soon after I joined, our foremost gun was removed and

replaced by an excellent quick firing twin 6-pounder gun which proved a

first-class weapon for the task. I thought it would be interesting to

record one action in which we were involved.

At 20:47 six E boats were illuminated by star shell at a range of about

3,100 yards (a mile and a half) and were engaged by all guns, and some

hits from the twin 6-pounder were observed. Shortly after this the E

boats withdrew. On resuming our course to the eastward, when still

about three and a half miles from the shipping channel, contact was

regained but some doubt existed as to whether this contact was the

enemy or not. Course was altered to close when the radar indicated that

there were several echoes which we believed were from another group of

E boats. Speed was increased and when the range was down to 2100 yards,

the target was illuminated by a star shell. It was then clear that this

contact was in fact a different group, and we opened fire with

everything we had, and hits were observed from our pom-poms and

particularly from our 6-pounder. Though so often in this sort of

warfare it is difficult to know just how well you have done, in this

case there was no doubt at all. One E boat was clearly sunk, and

another shortly blew up. In all it was a most satisfactory action from

our point of view. It was rather nice to learn later that Lieutenant C.

E. Tooley, for his most distinguished conduct, was awarded the

Distinguished Service Cross, and I was awarded a bar to mine."

This action took place on 22 December 1944 while HMS Walpole was escorting a convoy from the Thames to Antwerp. It was described on the front page of the Ely Standard on 29 December 1944, "HMS Walpole

in lively action: two E-boats sunk, others damaged." If Lt Cdr

Crowley's Report of Proceedings can be traced it will be added to this

page.

"Twin Six Pounder Crew sank two 'E' Boats"; the caption written by George C Crowley with these three names below

Fixter Sellars (Sub Lt B.C. Sellars RNVR) Green

Get in touch if you can you identify the other mermbers of the Gun Crew

Courtesy of Patrick and Roger Crowley

Guests from Ely

From time to time certain towns and districts were asked if they would

like to adopt a warship. It so happened that Ely and District was asked

if they would adopt HMS Walpole.

This offer came about as a result of Ely having contributed in Warship

Week the sum of £269,000 in March 1942 and they were thrilled at the thought of

adopting a destroyer. Apart from the exchange of a plaque from them and

the gift of the ship’s crest from us the matter seemed to have died a

natural death. This was not so however, as I and the wardroom, in

consultation with the ships company, agreed that we should ask for a

small team from Ely, possibly led by the bishop or dean, to come and

visit the ship, talk to the ship’s company and stay to lunch. I first

of all asked the captain (D) if it would be possible for the Walpole

to be in on a certain date and he assured me that, provided there was

no dire emergency, this could be arranged. We then sent an invitation

which was accepted with alacrity and in due course the great day

arrived. Led by the dean a party of ten arrived at Harwich on 8 December 1943 and came

aboard. The ship was at divisions and the Ely team were first of all

led around the Divisions and at each stop the dean gave some stirring

words of encouragement and thanks. After this there was an opportunity

for the visitors to look at the ship more closely and the was a

demonstration of gun drill. The chief boatswain’s mate, a Chief Petty

Officer, then gave the dean the boatswain’s call, which he was

delighted to receive. Then after half an hour or so, we gave the party

drinks in the Wardroom, followed by what in those days was a very nice

buffet lunch.

Find out more about Warship Week at Ely in March 1942 and the adoption of HMS Walpole

And see more pictures of Lt Cdr George Crowley's guests on their visit to HMS Walpole at Harwich in December 1943

From Lt Cdr G.C. Crowley's photograph album courtesy of Patrick and Roger Crowley

In these older ships it was necessary to have the boiler cleaned fairly

regularly, and on these occasions, we were berthed alongside at

Parkeston Quay. Here every opportunity was taken to give leave in two

groups, much of the cleaning being carried out by a shore team brought

in. Most ships, including Walpole, kept the chief engineer in the ship

for this period, leaving him behind for a similar period when the

cleaning was completed. It also gave us a chance to have minor defects

corrected.

Facilities ashore at Harwich were really quite good. There was a

cinema, one or two bars, a junior ratings club, something similar for

the senior rates, and a kind of club a few miles away for the officers.

I can well remember dropping a depth charge off the east coast which we

were allowed to do every six months. I though it a good idea if we

could manage to get some really fresh fish on this occasion, so I

selected where we would go to let off our six-monthly depth charge. God

must have been on our side as we killed more cod than I had ever seen

before. We simply raked them in and though many would say that cod is a

dull fish, all I can say is that when it comes straight from the sea

and into the pan it tastes delicious, and quite different from the

usual cod bought from a fishmonger which may have spent many weeks in

transit. We had so many cod that we were able to give some away to the

Ganges, the boys training establishment just across the water from

Harwich.

The Normandy Landings

As we ventured into 1944, the possibility of an invasion of Europe

became more and more likely. As we were more or less permanently on the

eastern side of the UK many of us began to wonder what the great masses

of extraordinary looking floating concrete boxes could be for. As

summer approached stacks of books and documents arrived, all sealed,

and not to be opened until ordered, the possibility of an invasion, at

least to me, became a certainty. Finally, I was ordered to open some of

the invasion orders which showed where it was going to take place. It

was interesting to note that even if the enemy had got hold of the

plans, he could not have known when the invasion was going to happen.

Furthermore, there was a great deal of evidence that it was likely to

take place in a different area. The amendments to these plans were

substantial, and I had to get one or two officers, sworn to secrecy, to

help me carry out the necessary corrections.

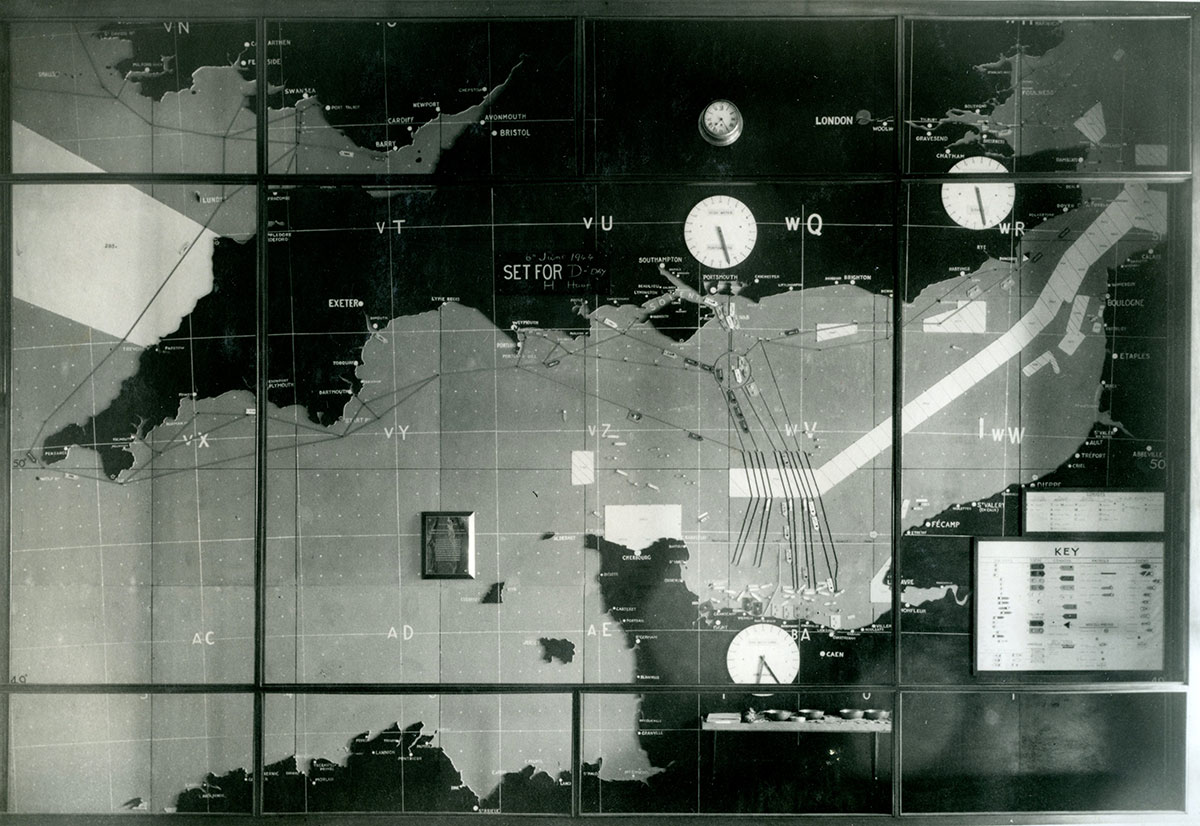

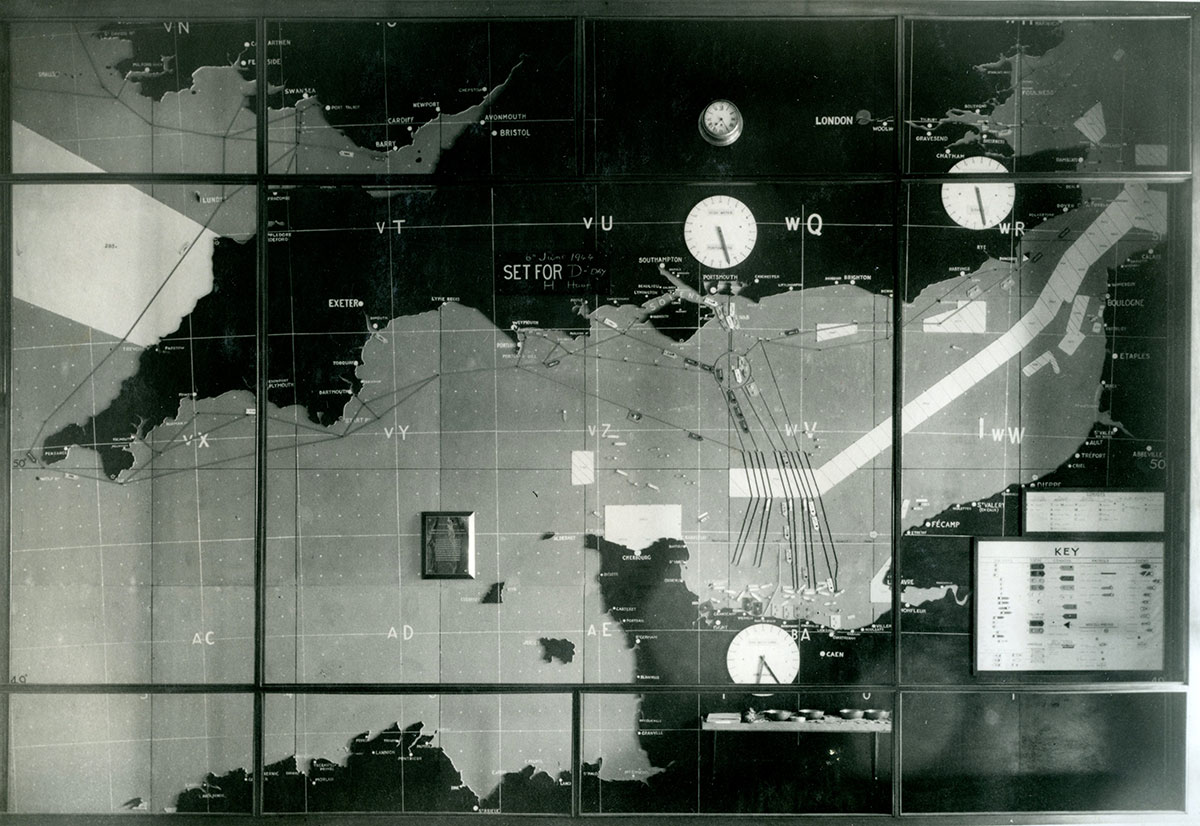

"D-Day map at HMS Dryad"

"D-Day map at HMS Dryad"

The Map Room in Southwick House HMS Dryad,

Hampshire, displays the actual map used during the D-Day landings in

Normandy and shows the positions of Allied Forces on 6 June 1944.

When the invasion started, Walpole

was due to escort a convoy on the beaches on D +3. As we were due

to start from the Harwich area, this meant that we had to leave at

least two days before. The routes were all clearly laid down and those

leading towards the landing areas were slightly different from those

leading away. This was to reduce the risk of collisions, since the

volume of shipping both inwards and outwards would build up

significantly. Despite a slight weather hitch which postponed the

starting date the invasion was on, and once the signal was made

initiating the start, any chance of stopping it, was impractical. The

routine was that we escorted the convoy, keeping the ships together as

closely as possible. I can remember quite clearly one American ship was

badly behind station, and after chivvying him up, he made a signal back

saying “don’t be too hard on me, I’ve only done a correspondence course

on this business”!

On arrival at the beach, the control of the ships

was taken over by the landing organisation, and the escorts were

required to report to a particular unit. We were then told where to

anchor and when we would be required again. On arrival we could see the

initial steps taken to build the prefabricated harbour, explaining what

the floating concrete boxes were for. All would be quiet during the day

apart from the odd air alert. As we now had definite air superiority

over that part of the Channel and landing beaches, there was little

interference. The when zero hour arrived, we weighed anchor and started

to round up our outward-bound convoy for the journey back. On arrival

off the east end of the Isle of Wight, ships bound for

Southampton/Portsmouth and the west were detached while we turned

eastward. Although I had expected the that all shipping bound for the

landing beaches would be attacked by all means possible, so far this

was not to be. At the same time, we had to be alert for attack from the

air, E boats, submarines, and not to be forgotten, mines. Though the

work of the escorts was hard, it was the greatest possible satisfaction

that the worm had at last turned and we were on our way back, not only

to Europe, but to victory.

There were three specific episodes that I can well remember. The first

was the effect of dense low-lying fog. Visibility was down to a few

hundred yards or less, and though by now we had radar, the density of

shipping was such that it was of limited value. The extraordinary thing

was that our aircraft overhead could see the shipping yet we could not.

However, fog seldom lasts for long and it was soon clear again. Some

say that it is seldom rough in the channel. Believe you me this is

simply not true, and it was not long after the initial landing that the

weather blew up to gale force winds and it became so rough when we were

anchored off the beaches, that it was quite impossible to get on to the

forecastle to weigh anchor. All we could do was raise steam and keep

the ship as steady as possible. Fair weather did arrive eventually and

things returned to normal.

The third strange thing happened was when we were proceeding in the

channel. To my amazement I saw a great ball of light looking like an

aircraft on fire rushing through the sky towards the English coast.

When I saw another and then another, I realised that they were a form

of enemy rocket or what we eventually called doodlebugs, when the

engine cut out, dived down to the land and exploded in a terrible

shattering bang. I reported this, but it soon became apparent the

authorities knew all about them.

One unusual event that happened was when my brother John asked if there

was any chance of his coming over to the invasion beaches in the

"Wallop’" I said that there would be no difficulty but I could not

guarantee that he would get back on my ship. He accepted with alacrity

and came over with us. He landed soon after we anchored and spent the

whole day prowling around looking at what was going on. Strange to say,

just as we were weighing anchor, a boat arrived alongside and John

stepped aboard. He had had a great day and had seen so much. The funny

thing was that though I had been over to the invasion coast so many

times, I never had the opportunity to land.

Looking back ...

Looking back on my life in the Walpole

I can remember two things that affected me. I used to wear a funny

little anorak thing which kept the upperpart of me nice and snug though

it really did not go down that far. I can recall when I was sitting

down in the wardroom and dozing off. When I woke up I could not get out

of my chair, I had more or less seized up. All the doctors said it was

a disc or something like it. Though after 24 hours I had more or less

recovered, it took me some years to throw off the trouble.

The other thing was that when I joined the "Wallop", my knowledge of

ship handling was very limited. However, after some months and a number

of not too serious bumps, I got better and better. One day, for no

apparent reason, I took Walpole

out of Harwich backwards. Destroyers have great power and once you have

confidence there is really very little you cannot do with them. The

only person who was a bit affronted was the Chief, who said in no

uncertain terms that I should not have done it without warning him

first.

We did quite a lot of entertaining on board, mostly Wrens, and I think

it would be fair to say that there was a tendency to entertain more of

the Wren ratings than the officers. There was a host of ratings

including plotters, boats’ crew, drivers, cinema operators and so on.

Many have asked me why I never got married in the war. I am not sure I

know the reason. I think I was afraid of getting married, having

children, and then getting bumped off. This partly because I felt I was

doing a good job, and if I was married, I would be less good at it, and

I suppose partly because I never found the right girl, though not for

want of trying!

Mined!

As the war crept on, we were gradually moved over to do more and more

work on the European side and soon we were patrolling off the Scheldte.

Looking back, I think I was very lucky during the war, but it always

seemed that sooner or later the dice would be loaded against me. So it

was, on the evening of 5th February 1945, that in the company of HMS

Rutherford we arrived on patrol 19 not too far from the Scheldte, with

Walpole stationed about a mile to seaward. This was on account of the

recent number of midget submarine attacks that had taken place in the

area. The patrol was uneventful until about 07:40 on the following

morning when the Officer-of-the-watch, the First Lieutenant, reported

something floating not far ahead. I was in the operation room at this

moment but on my way to the bridge. He followed up his report saying

that it was a mine. I heard the order “Starboard 30” followed almost

immediately by a tremendous explosion, when the whole ship seemed to

rise out of the water. It was clear that the mine had hit the ship

somewhere amidships. An emergency signal was sent to the Rutherford.

Already the ship was heeling over considerably. It was soon clear that

number 1 boiler room had been flooded and that all power had been lost.

When an old ship such as Walpole is hard hit there is usually a

considerable amount of damage. The Chief Engine Room Artificer, the

Chief having been left behind, arranged to shore up the bulkhead

between the flooded boiler room and the next compartment. Although

considerable efforts were made to try and raise steam in the other two

boilers they met with no success. In due course the ocean-going tug Saucy

took us in tow and we arrived in the vicinity of Sheerness. Tragically

we lost the crew of number 1 boiler room and all the usual steps were

taken to inform the authorities and the next of kin."

On 6 January 1945 HMS Walpole

detonated a mine off Flushing in the Netherlands killing two of the

crew, 38 year old PO Stoker Herbert John Reynolds (C/K 66673) and 18

year old Stoker 2nd Class Robert Patrick Emmett (C/KX 603469). Both are

buried in naval graves at Gillingham. HMS Walpole was taken back to Chatham where she was declared a

constructive total loss not worth repairing and sold to be broken

up for scrap on 8 February 1945.

Old Friends

"Alas, the end of the Walpole

was in sight and it was needless to say a sad parting for us all. Two

small things are perhaps worth recording. The first was that some time

before the wardroom had bought some quite attractive prints of old

ships but could not get them framed. I asked Mr Clements, the manager

of the boatyard if he could help get them framed and he agreed to frame

them in teak in exchange for a duty-free bottle of gin, which he did.

When it was decided that the ship was to be scrapped, I was asked if I

would now like to have the prints, and I said I would, and still have

them today. The other thing is that on one of the after-screen doors,

there was a brass plate of six inches in diameter which showed a

picture of a bell being rung by a hand, and in the centre of the bell

was another picture of a man clasping or wringing his hands. Though at

first we thought this was the crest of the First World War it now seems

more likely that this was in fact Walpole’s own crest. It is now

thought it was based on what Sir Robert Walpole said in 1739 on the

declaration of war with Spain “They now ring the bells, but they will

soon wring their hands”. I took this crest off the after screen and

still have it today."

CPO Ambrose Smith was allowed to take home the framed portraits of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth which had hung in the Wardroom of HMS Walpole and, probably, all of her His Majesty's Ships since soon after they were taken in 1941.

A typescript page from Lt Cdr George C Crowley's unpublished memoir

On looking back over my two years in Walpole I feel that I had been most fortunate. I had left a French Chaser and HMS Stanley just before both ships were lost with all hands. I was sunk in HMAS Nestor and suffered not a scratch, and though bullets had passed through the bridge on Walpole,

they had missed me. I had learnt a lot as well. I had to contend with

substantial pilotage problems, tides, currents and shoals. I learnt how

to handle a destroyer well, and now had two years’ experience of Action

Information and Plotting and had dealt successfully with many E boat

attacks. I also took part in one of the greatest invasions of Europe

and lived to tell the story. Finally, I had command of a happy and

contented ship which was also an efficient unit of the fleet."

HMS WALPOLE

HMS WALPOLE