This

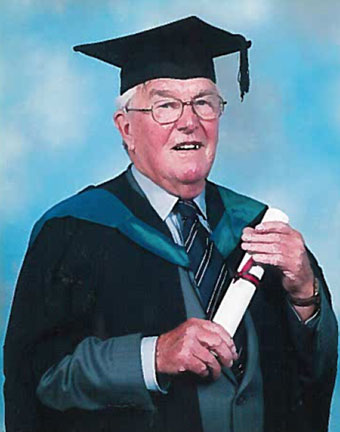

wonderful article was written first hand by Bill Riseborough, and sent

undated to Vic Green for publication in the Newletter of the V & W

Destroyer Association. Sadly, it was never published and Bill

Riseborough died at Swansea aged 91 in 2014. His son, Bill Riseborough

Jnr, rounds off his father's story at the end and provided the photographs.

William A. Riseborough was born on Friday 13 January 1922 and

attended a Grammar School from 1932-7. He was a talented artist

but:

"My

parents, mainly my mother I think, decided that I should sit the entry

examination for Royal Naval Artificer, a career geared to the sciences

rather than the arts. The Admiralty had, sensing the

imminence of war, decided on an intake of one hundred and eighty

Apprentices so in due course off I went to Chatham Barracks, Kent, on

17th August 1937, to join the Navy. After completing my apprenticeship as a "Tiffy", an Engine Room Artificer, I joined HMS Wanderer in July 1941 when I was nineteen."

HMS WANDERER

HMS WANDERER

"Their Lordships had no intention of letting us hang around in idleness

in Chatham Barracks and within days I was in the Drill Shed, teeming

with ratings awaiting transport to ships at sea. We ex Artificer

apprentices, now Electrical, Ordnance or Engineroom Artificers, were

drafted according to our surnames, the A`s to G`s going to Battleships

and Aircraft Carriers, H`s to L`s to Cruisers, M`s to P`s

to modern destroyers, with R`s like me getting the more ancient

vessels. The poor S`s onwards picked up the Corvettes and

Sloops.

"Their Lordships had no intention of letting us hang around in idleness

in Chatham Barracks and within days I was in the Drill Shed, teeming

with ratings awaiting transport to ships at sea. We ex Artificer

apprentices, now Electrical, Ordnance or Engineroom Artificers, were

drafted according to our surnames, the A`s to G`s going to Battleships

and Aircraft Carriers, H`s to L`s to Cruisers, M`s to P`s

to modern destroyers, with R`s like me getting the more ancient

vessels. The poor S`s onwards picked up the Corvettes and

Sloops.