The Netherlands was neutral in the First World War. Belgium, Luxembourg

and Switzerland were neutral by treaty but the Netherlands was neutral

by choice. Although the Dutch was not one of the belligerents it was

one of the first to mobilise and sent around 200,000 troop to defend

the Nineteenth century Waterline (

Waterlinie) and Amsterdam Fortifications (

Stelling van Amsterdam).

The Dutch managed to maintain its neutrality but had to cope with the

consequences of the war: refugees, food shortages and the need to

intern soldiers or sailors - from both sides - who happened to end up

in Dutch territory.

After the war, the Dutch gave the deposed Kaiser Wilhelm II refuge. He lived out his days at Doorn House (

Huis Doorn)

until his death in June 1941 in German occupied Netherlands. This was

not the first time the Dutch had helped Britain’s enemies. In

1900, the cruiser (

pantserdekschip)

Hr.Ms.Gelderland,

was sent - with British agreement - to take Paul Kruger, President of

Transvaal, one of two Boer states at war with Britain, to exile in the

Netherlands. He was received by Queen Wilhelmina, and stayed in the

country until a couple of months before his death in July 1904. Several

streets in the Netherlands are still named after Kruger or othe Boer associations. Almost forty

years after Kruger’s arrival, the Queen who gave him refuge would seek

her own safety, in Britain, and was taken there by the destroyer HMS

Hereward.

After the Great War many Austrian and Hungarian children were fostered by Dutch

families and some settled in the Netherlands. After Hitler came to power, a

new influx of refugees came to the Netherlands from Germany, mainly

Jews, including the family of Anne Frank.

By the late 1930s, the Dutch state was understandably nervous about the

international situation. It desperately wanted to maintain its

neutrality and forbade any joint planning with the Allies to

prepare for its defence lest this provide an excuse for an invasion.

The seizure in November 1939 of two British agents five metres from the German border at

Venlo led to the head of Dutch military intelligence

losing his position. The so-called "Venlo incident" was used by the German Nazi

government to link Britain to Georg Elser's failed assassination

attempt on Adolf Hitler and help justify Germany's invasion of the

Netherlands.

In the run up to war, The Netherlands’s rearmament programme came too late. The greatest

deficiency was the complete lack of tanks. The country hoped that

its neutrality would be respected and that if an invasion occurred its

defences based on static fortifications and flooding, would hold out

until the Allies came to their assistance. None of these hopes were

justified.

The Whitsun invasion

In the early hours of Friday 10 May 1940, Germany launched

Fall Gelb

(Operation Yellow), its attack on western Europe, through the

Netherlands and Belgium. There were four main thrusts to the attack on

the Dutch. The first involved landings by paratroopers in the

west of the country. One of the main objectives was the capture of

airfields near The Hague that could, then be used to bring in troops by

plane, so-called airlanding troops. Other paratroopers were tasked with

capturing the Royal Family and leading members of the government.

Further south, paratroopers sought to capture airfields and strategic bridges in and around Rotterdam, including an audacious

coup de main involving seaplanes which landed on the New Maas river (

Nieuwe Maas) in the centre of the city and captured a major bridge.

These airborne units were to hold their positions until the arrival of

the main infantry and armoured units. These attacked along three axes.

One went through the south of the country and then swung north to

approach Rotterdam, relieving the paratroopers who had

secured the strategic bridges. The idea was to unlock the so-called

“Fortress Holland” (

Vesting Holland), a stronghold that also included The Hague and Amsterdam.

The other German advances were through the middle of the country, to

Utrecht and to the North. The latter was halted at the eastern end of

the

Afsluitdijk, the barrier that separated the Wadden Sea from the Zuiderzee. Had the Germans succeeded in taking both ends of the

Afsluitdijk, they could have threatened Amsterdam from the north.

The German paratroop and air landings around The Hague met with mixed

success. Some of the follow-up transport planes had to land on beaches,

motorways or fields, rendering most of them useless for collecting

reinforcements from Germany. Others had to land on airfields that were

unsafe, and planes were damaged as they landed. Some paratroopers were

dropped in the wrong place but the presence of so many airborne troops

in the lightly defended western flank caused the Dutch lots of

problems, even if the German objectives were not always secured.

Actions around Rotterdam were far more successful and arguably, of

greater strategic value, especially after the failure to capture the

heads of government or the Royal Family. They were evacuated to

Britain, for the most part with British assistance, leaving General

Henri Winkelman, Commander-in-Chief of Land and Naval Forces, as the

senior representative of the Dutch state in the country.

The Dutch put up stiffer resistance than expected but the Germans were

advancing on almost every objective. The Dutch air force was

non-existent, and following the bombing of Rotterdam on the 14 May, to

avoid further attacks on population centres,

General Winkelman decided the armed forces in the Netherlands would

“capitulate” - not surrender. The distinction was important, the

government did not surrender and armed forces abroad would continue the

struggle.

After five days of fighting, the Germans were able to take over the

Dutch mainland and adjoining islands. The invasion gave German forces

room to attack Belgium from the north whilst simultaneously acting as

bait to attract the Allies to advance north, a point of contention

between the British and French. Securing the Netherlands also gave

Germany access to air and naval bases closer to Britain from where

attacks could be launched.

The Royal Navy in the Netherlands, May 1940

No plans were made with the Allies to prepare for a German

invasion in order to protect Dutch neutrality. Unilateral plans were

made. For example, the Dutch Navy planned to relocate ships to Britain,

and British naval officers carried out surreptitious reconnaissance

missions to Dutch ports with a view to possible demolition work.

When the invasion took place, all Britain could do was retrieve what it

could from a bad situation. France sent troops into the southwest of

the country, the province of Zeeland, and attempted to relieve

Dordrecht, an important German objective south of Rotterdam.

British action concentrated upon evacuating people. These included

refugees fleeing the Germans (especially Jewish civilians, both German

and Dutch), diplomats and officials from various nations, Dutch

ministers and officials and the Dutch Royal Family. The Sadler’s Well

Ballet on tour in the country and including Dame Margot Fontaine, was evacuated. So were 1,300 German

troops captured by the Dutch, including a regimental commander, at that time the

most senior German in British hands.

Other actions related to the recovery of assets. As well as industrial

diamonds, the gold reserves in Amsterdam were successfully

shipped out but gold reserves in Rotterdam were not recovered, and an

attempt to retrieve securities and bonds from the Bank of the

Netherlands in Amsterdam also failed.

Finally, small British forces landed at the ports of IJmuiden,

Flushing, the Hook of Holland and Rotterdam. They were tasked with

destroying anything of value to the enemy, principally oil stocks and

port installations. A composite battalion of Irish and Welsh Guards

landed at the Hook to provide support for the evacuation of the British

diplomatic mission in the Hague, British expatriates and the Dutch

government.

Despite its other wartime commitments, including the evacuation of

troops from Norway, more than sixty British vessels were sent to the

Netherlands during the five day invasion. They ranged from

requisitioned ferries acting as troopships, through to trawlers acting

as minesweepers, MTBs (Motor Torpedo Boats), destroyers and a few light

cruisers.

This motley collection of ships found themselves in the major ports and

harbours of Den Helder, IJmuiden (at the mouth of the Amsterdam ship

canal, the Noordzeekanaal), Scheveningen (The Hague), Hook of Holland,

Rotterdam and Flushing, carrying out one or more of the rescue and

recovery tasks. The MTBs actually sailed up the

Noordzeekanaal into the

IJsselmeer and ended up being among the final units to leave for

Britain.

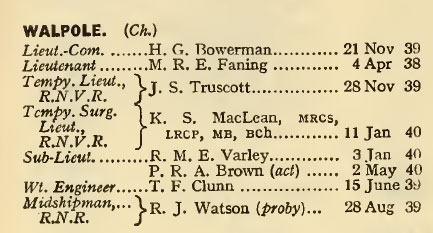

The backbone of the Royal Navy’s commitment to the Netherlands was the

destroyer force. Given how stretched the Navy was, to put together such

a large force was no mean feat. The destroyers were close at hand, the

Nore Command at Harwich and Dover Command. Some 23 V&W destroyers took part in

Operations off the Dutch, Belgian and French Coast (ADM 199/667) in May 1940. They were twenty years old and out of

date, their powerful 4.7-inch guns comparable with some light cruisers

were no defence against attack from the air. They often had to depend

upon the seamanship of the captain, or luck, to survive an air attack

unscathed. Yet, with their high speed were ideally suited for the high

tempo shuttle actions of those early May days.

HMS

Walpole had a simple task,

to transfer three individuals from Harwich to IJmuiden on the night of

Sunday 12th May to Monday 13th May (which would have been the Whitsun

Bank Holiday) and bring them back on Monday evening. IJmuiden was, and

still is, a fishing, ferry and steel port at the mouth of Amsterdam’s

ship canal, the

Noordzeekanaal.

Aerial view inland from IJmuiden on the Noordzeekanaal to Amsterdam

Aerial view inland from IJmuiden on the Noordzeekanaal to Amsterdam

The Netherlands Institute of Military History Collection

In 1940, the Diamond Trading Company in London was the centre of the

global diamond trade, with Amsterdam and Antwerp the centres of cutting

and finishing for both jewelry and industrial diamonds. Small in size,

the inherent value of industrial diamonds was vastly outweighed by what

they could bring to the war effort of whoever possessed them.

Industrial diamonds have the necessary physical characteristics to be

effective in the manufacturing processes of a range of objects. These

include aeroplane engines and related machinery, artillery, gyroscopes,

tanks and torpedoes, prisms and lenses for gun and bombsights.

The three passengers on HMS

Walpolewere

tasked with recovering as many industrial diamonds from Amsterdam

as they could. Two of the party were employees of J.K. Smit en Zonen,

at that time one of the largest diamond companies in the world. The other was a

member of the British secret service. J.K. Smit en Zonen was an

international company with an office in London. Two of its Dutch

representatives in Britain, Jan Kors Smit and Willem Woltman, joined

HMS

Walpole.

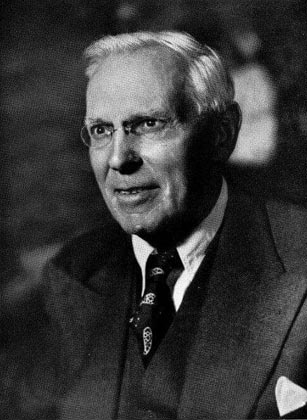

Jan Kors Smit (on left) was the grandson of the company’s founder, Jan

Kors, and son of the current head, Mr. Johan J. Smit (on right) in

Amsterdam. Both photographs are courtesy of JK Smit Diamond Tools.

The third member of the group was Lt. Col. Montagu Reaney Chidson, a

much-storied man. He was originally an officer in the Royal Garrison

Artillery, but was one of the earliest military pilots, gaining his

wings before the First World War. Come 1940, Chidson was part of

Section D of MI6, the template for the Special Operations Executive,

SOE. Chidson’s military and intelligence connections with the

Netherlands dated back to the First World War and immediate post-war

period. In the late 1930s he returned to the country as Passport

Control Officer in The Hague. This was the cover post for the local

head of MI6, the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS). His successor was

one of the two SIS officers kidnapped in the German intelligence coup at the Dutch border town of Venlo in November 1939.

The improvised and secret nature of the diamonds operation means that there is

virtually nothing written down in official (British) documents. HMS

Walpole received no written orders, there are no ship’s logs to refer to and, apparently, no after action report from

Walpole. HMS

Walpole

and its passengers are absent from the reports of Dutch naval and

military officers in IJmuiden during the German invasion and from

Commander Goodenough’s report on Operation XD(A), to destroy fuel reserves at Amsterdam and block the harbour at IJmuiden.

The frustration is all the greater because the vessels involved in

other sensitive missions to IJmuiden, such as the evacuation of Crown

Princess Juliana and her family, are mentioned. Further, the ship and

army officer tasked with recovering bonds and securities from the Bank

of the Netherlands (

De Nederlandsche Bank) are also mentioned in these military and naval reports … but not

Walpole nor her passengers.

However, at the highest level of government, the recovery of the

industrial diamonds was mentioned, for example, in para 4 of

"Operations off the Dutch and Belgian Coasts" in the

Weekly Resume (no.37) to the Cabinet Office of the Naval, Military and Air Situation from May 9th to May 16th 1940 (

The National Archives, CAB 66/7/38):

"Three Dutch merchant vessels with

bullion were safely escorted to the United Kingdom, but a small Dutch

pilot vessel with some bullion on board was sunk between Rotterdam and the Hook. Diamond stocks were also transferrd to the United Kingdom [our emphasis]. A

number of Dutch merchant ships was evacuated from Dutch ports, and the

SS Phrontus arrived in the

Downs with 900 prisoners of war. Refugees were evacuated from Dutch

ports, and on the 13th May HM the Queen of the Netherlands arrived at

Harwich in HMS Hereward; the

remainder of the Royal Family, the Dutch Government, Diplomatric Corps

and Legation Staffs of the Allies also safely arrived in the United

Kingdom."

The recovery of diamonds during operations in the Netherlands was reported in the British and Empire press, even being

briefly mentioned as far away as Australia.

Snippets of documentation surrounding the diamonds mission come from

the secretive Section D of MI6. Given the secrecy surrounding both the

expedition and of Section D, this is ironic. In particular, the

recovery of industrial diamonds from Amsterdam is mentioned in its

final report a few months later, summer 1940.

The mission is also recorded in the Dutch Official History of the Second World War, Dr. L. de Jong’s,

Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden in de Tweede Wereldoorlog,

but it takes up less than a page in a twelve volume work. Written

nearly thirty years later, Volume III, May 1940, covers the German

invasion and includes a precis of the expedition and mentions that

Walpole

was involved (pp.441-2). The participation of Willem Woltman is not

mentioned. It is a hallmark of the various sources, that they nearly

all mention two diamond merchants or Mr Jan Kors Smit and an

accompanying British intelligence officer, but not all three.

Panoramic view of the damage done to the houses along the Blauwburgwai, Amsterdam, following the German bombing on 11 May 1940

Panoramic view of the damage done to the houses along the Blauwburgwai, Amsterdam, following the German bombing on 11 May 1940

Source: Stadsarchief Amsterdam

Despite the lack of documentation, the balance of evidence suggests that three men on a secret mission travelled on the

Walpole

to IJmuiden on the night of 12-13 May 1940 and managed to get to

Amsterdam. On arrival in Amsterdam, Jan Kors Smit arranged a meeting with his father, Johan Smit,

the head of the family firm and

explained their mission. He had already managed to secure

passage for some of his diamond stocks the previous evening, handing

them over to a British merchantman on the evening of 12 May. He now

agreed to hand over the remainder of J.K. Smit en Zonen’s stock to his

son and companions, but not those upon which German interests had

options, much to the annoyance of Lt. Col. Chidson. Johan Smit also

facilitated a meeting with other diamond merchants in the city, two of

whom agreed to hand over diamonds. Their contribution to the haul was

much smaller than that of J.K Smit en Zonen (de Jong,

Koninkrijk,

op cit pp.141-2).

In the meantime, HMS

Walpole’s

was tasked with keeping out of trouble, and collecting the trio later

that day, 13 May. IJmuiden was subject to regular air attacks, so staying there was

not an option. Sailing up and down the coast also presented challenges

from a German Luftwaffe now enjoying air supremacy. According to the dramatised tale of the mission,

Adventure in Diamonds, HMS

Walpole

sailed south along the coast, near Scheveningen, The Hague’s own

harbour, where they would have seen plenty of evidence of fighting.

German transport planes carrying airlanding troops had landed on nearby

beaches as the airfields they were meant to land at were still being

contested.

The Netherlands Institute of Military History Collection

The Netherlands Institute of Military History Collection

managed to keep out of

trouble and made her way back to IJmuiden for her rendezvous with the

diamond party. Her three charges made their way back to IJmuiden from

Amsterdam as planned, having also brought with them a bottle of

Napoleon brandy each. The transfer to

HMS

Walpole was not without difficulty, requiring the

unwilling co-operation of a tugboat master, but they arrived back in

Britain early the next morning. Valuations of the diamonds they brought

back have varied from £500,000 to £2.5 million.

|

|

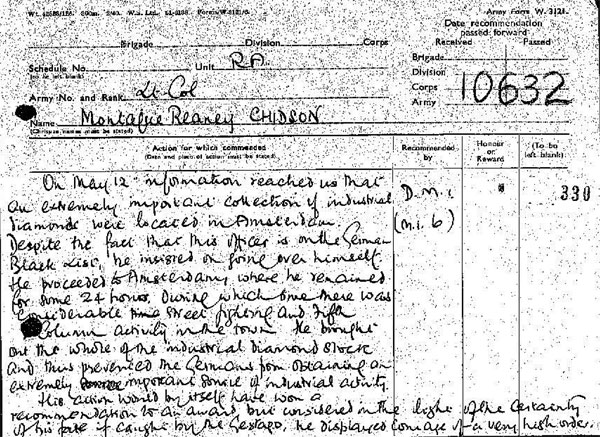

“On May 12 information reached us that an extremely important collection of industrial diamonds were located in Amsterdam.

Despite the fact that this officer is on the German Black List, he

insisted on going over himself. He proceeded to Amsterdam where he

remained for some 24 hours during which time there was considerable

street fighting and Fifth Column Activity in the town. He brought out

the whole of the industrial diamond stock and this prevented the

Germans from obtaining an extremely important source of industrial

activity.

This action would by itself have won a recommendation for an award but

considered in the light of the certainty of his fate if caught by the

Gestapo, he displayed courage of a very high order.”

|

|

The recommendation by DMI (MI6) for the award of the DSO to Lt Col M.R. Chidson was granted and announced in the London Gazette on 20 December 1940

This unsigned note from MI6 is in sharp contrast to the formal Reports of Proceedings with recommendations for awards made by Commanding Officers to the Admiralty

National Archives WO-373-16-272

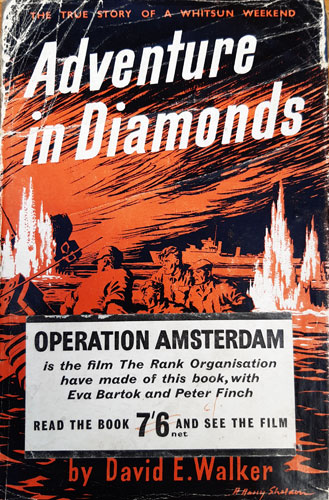

An exaggerated story?

Walpole’s

mission to bring the industrial diamonds from Amsterdam to Britain

during the Dutch five days war is mainly remembered today because

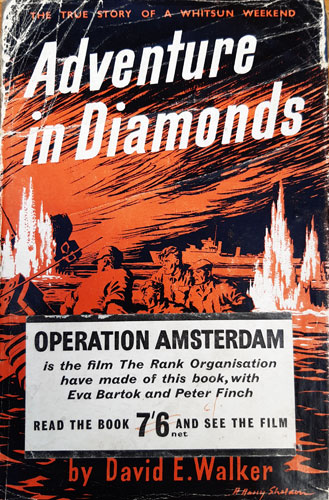

of a book by the journalist and author, David Esdaile Walker (on right). He was

born in Darjeeling, India, in 1907, the only child of Major General Sir

Ernest Walker, but was educated in Britain.

During the war he combined jobs as foreign correspondent for the

Daily Mirror

and a representative of the Reuters news agency for the Balkans with

work as an agent of MI6 in Switzerland, the Balkans and Greece and this

provided the background for several of his books. His eighth book,

“Adventure in Diamonds”

(Evans Brothers, 1955), is a dramatised account of the mission to

recover the industrial diamonds from Amsterdam. The book was a success

and reached an even larger larger audience when it was filmed by J

Arthur Rank and released as

“Operation Amsterdam” (1959). His novel "

Lunch with a stranger"

(Alan Wingate, 1957) is thought to be partly autobiographical, based on

his own activities as an MI6 agent under the guise of being a foreign

correspondent for the

Daily Mirror.

In Print - Adventure in Diamonds

Although long out of print second hand copies can be bought over

the Internet and an e-book version can be read online by clicking on

the link:

https://archive.org/details/adventureindiamo009653mbp/page/n8/mode/2up

Walker’s story centres on three individuals:

Mr Jan Kors Smit, Dutch, a director of J.K. Smit en Zonen in Britain, and grandson of the company’s founder

Mr

“Walter Keyser” [pseudonym for Willem Woltman], Dutch by birth but with

British nationalty and based in Britain, a colleague of Jan Kors Smit

“Major Dillon” [pseudonym for Lt. Col. Chidson], a British soldier with a clear secret service, or similar connection.

Significant roles are also played by:

Mr. Johan J Smit, Dutch, head of J.K. Smit en Zonen in Amsterdam. He is the son of the founder

and father of Jan Kors Smit in London.

Lt Cdr Harold Bowerman, captain of HMS Walpole.

When news reached Britain of the German invasion on Friday 10 May 1940

Jan Kors Smit and “Keyser”, aware of the value Amsterdam’s stocks

of diamonds could be to the German war effort, make their concerns

known to the Board of Trade. They are brought into contact with “Major

Dillon” and the three make their way to Harwich where they board HMS

Walpole,

which has been tasked with taking them to IJmuiden and back. The

destroyer leaves on the night of Sunday 12 May 1940 with all haste. On

the way across the North Sea it nearly collides with two other

destroyers travelling equally fast but towards Britain carrying the

Dutch Crown Princess and her family. At dawn on 13 May 1940, Walpole

arrives at IJmuiden.

The three companions disembark via rowing boat but, almost immediately, the

harbour is attacked by the Luftwaffe, which sinks a civilian liner

carrying refugees. However, our party succeeds in getting ashore only

to be met by scenes of chaos: Dutch soldiers everywhere, dead bodies

piled up, harassed officers and officials, refugees and the

ever-present fear and threat of fifth columnists and German

paratroopers.

The party also meet the mysterious “Anna” who has just seen the parents

of her fiance killed by a German air attack as they were leaving by

trawler. She agrees to take the three to Amsterdam in her car.

In Amsterdam, they meet with one of “Major Dillon’s” contacts and with

Mr Johan J. Smit, head of the J.K. Smit en Zonen diamond company. He

had

already delivered a package of diamonds the previous night to a British

merchant ship and agrees to hand over his remaining diamonds and ask

other diamond merchants if they will hand over their stocks. The

Amsterdam and Antwerp diamond industries were predominantly Jewish

(although the Smit family is not). They were naturally nervous of the

situation and of reprisals if they assisted the British, but at a

subsequent meeting many are reassured and hand over their diamonds to

Jan Kors, “Keyser” and “Major Dillon”.

They return to IJmuiden with the diamonds, avoiding some traitorous

Dutch soldiers on the way with a little help from “Anna’s” boss who is actually a

Dutch Colonel. Despite the chaos and panic in the town they manage to

rejoin

Walpole, but not

without some officious difficulty involving a tug master who refuses to

leave the harbour because he is not qualified for ocean going. This is

resolved after some not so gentle “persuasion” by “Major Dillon”.

Walpole had been sailing up

and down the Dutch coast near Scheveningen and The Hague and had

encountered other destroyers, a merchant ship carrying gold to Britain

and seen evidence of the fighting inland. Having embarked her

passengers from the harbour tug,

Walpole makes it safely back to Britain and the diamonds are handed over to the care of The Diamond Trading Company in London.

After allowing for the exaggerations, sensationalism and the fictional

details required in a novel the book can still be considered a guide to

actual events though not all details are accurate. Walker assures the

reader of the co-operation of the protagonists and some content can

only have come from first-hand accounts by “Keyser” (Willem Woltman),

Lt.Cdr. Bowerman and Johan Smit. “Major Dillon” (Lt.Col. Chidson)

considered himself bound by the Official Secrets Act and declined to

assist. Since Jan Kors Smit died in 1946 his real name could be

used in the book.

On Film - Operation Amsterdam

Walker’s book reads as if written for a screenplay and soon after

publication the film rights were acquired by the Rank Organisation and filmed

at Pinewood Studios and on location in IJmuiden, Schermerhorn and in Amsterdam. It was released in 1959 as

Operation Amsterdam

and starred Peter Finch, Tony Britton, Eva Bartok and, in supporting

roles, Melvyn Hayes and John Le Mesurier. It can be viewed (writing

mid-2020) on YouTube at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HYnwG73Z9Aw

Filming “Operation Amsterdam” in IJmuiden harbour

Filming “Operation Amsterdam” in IJmuiden harbour

Peter Finch (Jan Kors Smit) is left foreground holding a white

package, Alexander Knox (Walter Keyser) is centre foreground

squeezing between two actors, Tony Britton as “Major Dillon” is

in front of the camera

Noord-Hollands Archief (Ref. KNA001005559)

While based on Walker’s book, the second half of the film veers even

further away from his dramatised account. For example, there is a

fire-fight between soldiers, all in Dutch uniform, a fully functioning

resistance cell equipped with German weapons (the Germans only arrived

in Amsterdam on 15 May 1940 and our story takes place on 12-13 May) and

the diamonds are stolen from a bank vault. None of this, of course,

actually happened. Unfortunately, the role that

Walpole plays in the film is marginal.

The film made a substantial contribution to the mythology surrounding the expedition. Its title “

Operation Amsterdam”

is assumed to be the actual name of the mission. Given its hurried,

secret and ad hoc nature, the expedition might not have had a formal

name. There is no evidence for a mission name and it is not mentioned

anywhere in the book “

Adventure in Diamonds”. However, when the book was reprinted in the 1970s, some editions at least were published with the title “

Operation Amsterdam”.

Legend and Myth

HMS Walpole was adopted by the town of Ely in the Fen country of Cambridgeshire

as the result of a successful Warships Week national savings programme

in March 1942 which raised £300,000 for the construction of a new

destroyer. When a civic deputation visited Walpole from Ely in late 1943, the Ely Standard reported on its front page that Walpole had saved the Dutch Crown Jewels. Walpole’s

voyage to Holland on 12 May 1940 had become part of the ship’s

folklore, passed on from shipmate to shipmate and were repeated by the Ely Standard three and a half years later.

Although Walpole’s

return cargo had morphed into the Dutch Crown Jewels this is actually

one of the few references outside of Walker’s book of the ship’s

involvement in those mad May days of 1940. The three individuals

brought back with them industrial diamonds worth perhaps as much as

£2.5 million in current prices and vastly more today. And in June 2020

the Ely Standard published a further article about these latest discoveries.

Another memento of Walpole’s

journey can be found in Gerrards Cross, Buckinghamshire, where Jan Kors

Smit, one of our travellers, lived. He renamed his home - which later

also served as an address for J.K. Smit en Zonen - Walpole House

in honour of the trip he undertook in 1940. After Jan Kors’ death his

brother Johan Jnr lived there. When he died more than fifty years after

these events, he was recorded as living at “Walpole Cottage”, a

different address but still bearing the Walpole name. . Quite clearly,

this ship, her actions, and

this expedition in May 1940 left an indelible impression on the Smit

family.

***************

A similar "mission" took place in

Antwerp, second only to Amsterdam in diamond

cutting, polishing and fashioning. It is much is better documented as

the protagonist wrote it all down, in English, some three years later.

On 11 May 1940 Paul J. Timbal, the CEO of the

Antwerp "diamond bank" and a Belgian Army reservist, left Antwerp with

100 million Belgian Francs (around 67 million Euros) of diamonds for

Paris. He was accompanied by his wife and two daughters, and arrived

two days later. Concerned about

the safety of Paris, he moved on to Royan at the mouth of the Gironde

near Bordeaux, but with the fall of France imminent decided to move on

again to Britain.

Operation Ariel was the code name for the evacuation of troops and civilians from the western ports of France between 15 - 25 June 1940. By this time, MI6 was aware of what Timball was doing and sent the steamship Broompark to bring him to Falmouth. Lord "Wild Jack" Suffolk

organised the evacuation of Timbal and French nuclear scientist with

heavy water. Three years later Timball wrote a 353 page book, published

in English in 2014 by the Belgian Royal Commission on History with the

title, "Why the Belgian Diamonds Never Fell Into Enemy Hands, May 10, 1940 - June 23, 1940" (Commission

royale d'histoire, 2014). The Bartlett Maritime Research Centre in the

National Maritime Museum Cornwall, Falmouth, has published an online

account of the Broompark's arrival at Falmouth with the diamonds and heavy water.

If you can provide further details of the diamond mission or have any queries about it contact Darron Wadey by e-mail.

Darron is a British national

resident in the Netherlands. He is a member of a number of (military)

historical associations and societies.

His research concentrates upon British actions during the invasion of the Netherlands in May 1940.

HMS WALPOLE

HMS WALPOLE

The Netherlands was neutral in the First World War. Belgium, Luxembourg

and Switzerland were neutral by treaty but the Netherlands was neutral

by choice. Although the Dutch was not one of the belligerents it was

one of the first to mobilise and sent around 200,000 troop to defend

the Nineteenth century Waterline (Waterlinie) and Amsterdam Fortifications (Stelling van Amsterdam).

The Dutch managed to maintain its neutrality but had to cope with the

consequences of the war: refugees, food shortages and the need to

intern soldiers or sailors - from both sides - who happened to end up

in Dutch territory.

The Netherlands was neutral in the First World War. Belgium, Luxembourg

and Switzerland were neutral by treaty but the Netherlands was neutral

by choice. Although the Dutch was not one of the belligerents it was

one of the first to mobilise and sent around 200,000 troop to defend

the Nineteenth century Waterline (Waterlinie) and Amsterdam Fortifications (Stelling van Amsterdam).

The Dutch managed to maintain its neutrality but had to cope with the

consequences of the war: refugees, food shortages and the need to

intern soldiers or sailors - from both sides - who happened to end up

in Dutch territory.

The three passengers on HMS Walpolewere

tasked with recovering as many industrial diamonds from Amsterdam

as they could. Two of the party were employees of J.K. Smit en Zonen,

at that time one of the largest diamond companies in the world. The other was a

member of the British secret service. J.K. Smit en Zonen was an

international company with an office in London. Two of its Dutch

representatives in Britain, Jan Kors Smit and Willem Woltman, joined

HMS Walpole.

Jan Kors Smit (on left) was the grandson of the company’s founder, Jan

Kors, and son of the current head, Mr. Johan J. Smit (on right) in

Amsterdam. Both photographs are courtesy of JK Smit Diamond Tools.

The three passengers on HMS Walpolewere

tasked with recovering as many industrial diamonds from Amsterdam

as they could. Two of the party were employees of J.K. Smit en Zonen,

at that time one of the largest diamond companies in the world. The other was a

member of the British secret service. J.K. Smit en Zonen was an

international company with an office in London. Two of its Dutch

representatives in Britain, Jan Kors Smit and Willem Woltman, joined

HMS Walpole.

Jan Kors Smit (on left) was the grandson of the company’s founder, Jan

Kors, and son of the current head, Mr. Johan J. Smit (on right) in

Amsterdam. Both photographs are courtesy of JK Smit Diamond Tools.

Although long out of print second hand copies can be bought over

the Internet and an e-book version can be read online by clicking on

the link: https://archive.org/details/adventureindiamo009653mbp/page/n8/mode/2up

Although long out of print second hand copies can be bought over

the Internet and an e-book version can be read online by clicking on

the link: https://archive.org/details/adventureindiamo009653mbp/page/n8/mode/2up