Click on the links within this brief

outline for first hand accounts by the men who served on HMS Woolston and for a more detailed chronolgy see www.naval-history.net

HMS

Woolston was one of six Thornycroft W-Class destroyer built at Thorneycroft's Woolston

shipyard on the opposite side of the River Itchen from Southampton. She

was launched in January 1918 and named after the shipyard where she was built. The Woolston made news when she entered Scapa Flow with Harry Hawker and Cdr Kenneth Mackenzie-Grieve

after their unsuccessful attempt to fly across the Atlantic in May

1919. From 1926 - 8 HMS Woolston was part of the 3rd Destroyer Flotilla on the China

Station but in August 1927 she was put in Reserve until 1931. Her CO, Lt Cdr Donal Scott McGrath RN became CO of HMS Wanderer and remained on the China Station with the 3rd DF. On 11 September 1931 HMS Woolston was commissioned at Devonport for service with the First Anti-Submarine Flotilla out of Portland.

In 1939 she

was converted to a WAIR type Anti-Aircraft (AA) escort (her pennant

number changed to L49) and spent most of 1939 - 42

escorting east coast convoys in the North Sea. Her first wartime CO, Lt

Cdr W.J. Phipps RN, described this period in his diary (Imperial War Museum, Docs.7510) and a CW Candidate, Samuel Gorley Putt, described life as a rating on the lower deck of HMS "Tiddley" (Woolston) in Men Dressed as Seamen (1943). In March 1941 Woolston

was transferred to Western Approaches Command at Londonderry as an

Atlantic escort but returned to Rosyth Command escorting east coast

convoys in November 1941. During National Warships Week in February

1942 the

Cheshire town of Congleton adopted HMS Woolston

after raising £220,000, the cost of building the

hull of a destroyer. In March she was

part of the escort for Arctic Convoy PQ.12 and returning Convoy PQ.8.

In June and July of 1943 HMS Woolston (Lt Frederick William Hawkins RN) escorted convoys to Gibraltar and the

invasion beaches on Sicily, Operation Husky.

From 1944-5 she resumed her service as an escort for east coast convoys

and the war artist, Charles E. Turner,

spent some on HMS Woolston

during this period. At the end of the war she made two trips to Bergen, Norway, Operation Conan (part of Operation

Apostle) to accept the surrender of German naval forces. HMS Woolston was paid-off and reduced

to Reserve status after VJ Day and broken up in 1947.

Commanding Officers

With acknowledgement to the Dreadnought Project and Unithistories.com

Officers

This

short list of officers who served on HMS Woolston during World War II all

have entries on the unithistories.com web site.

Further names from the

Navy List will be added later.

| Lt Thomas Johnston RN (April - October 1938) Wartime Officers Lt. A.H.G. Butler, RNVR (11 May 1943 - April 1944) Lt Ian N.D. Cox, RN (31 July - Dec 1941) S.Lt John P.O. Evans, RNVR (15 September 1939 - Dec 1941) |

A. Hugo E. Hood, RN (11 Sept - Oct 1942) Lt(E) C.A. Maxwell, RN (1942/3?) Lt. Herbert A. Taylor, RN (4 March 1943 - Dec 1943) Lt. Basil C.Ward RN (9 Sept 1939 - 13 August 1941) Cd. Gnr Harold West RN (March - April 1930) Lt. Roderick B. Whatley, RN (27 March 1942 - Feb 1943) |

Transatlantic aviators saved by Woolston in 1919

Everybody

knows that John Alcock and Arthur Brown made the first non-stop

transatlantic flight in June 1919 in a modified First World War Vickers

Vimy bomber and the Secretary of State for Air, Winston Churchill,

presented them with the Daily Mail prize for the first crossing of the

Atlantic Ocean by aeroplane in "less than 72 consecutive hours".

Everybody

knows that John Alcock and Arthur Brown made the first non-stop

transatlantic flight in June 1919 in a modified First World War Vickers

Vimy bomber and the Secretary of State for Air, Winston Churchill,

presented them with the Daily Mail prize for the first crossing of the

Atlantic Ocean by aeroplane in "less than 72 consecutive hours".

But they were so nearly beaten by the Australian pilot, Harry Hawker (on left), and his navigator, Lt Cdr Kenneth Mackenzie-Grieve RN (on right), who set off from Newfoundland on 18 May 1919 in their Sopwith biplane named Atlantic but had to ditch in the Atlantic after fourteen hours. They were rescued by the Danish ship, Mary, which had no wireless to report their rescue and it was assumed they died when their plane crashed in the sea.

HMS Woolston, the Navy's newest destroyer, had "short legs" and never crossed the Atlantic but she was in the area and had wireless communication. The Mary transferred the brave aviators to the Woolston who reported their rescue and took them to Scapa Flow. The Illustrated London News carried the news to their readers in their issue of the 31 May:

"The steamer Mary which rescued Mr Hawker and Commander Mackenzie-Grieve RN, was intercepted on May 25th off Loch Erribol by the destroyer Woolston which conveyed them to the fleet at Scapa Flow, where they spent the night on board HMS Revenge as the guests of Admiral Freemantle."

One of Frank Witton's shipmates in HMS Woolston was

"Eboat", the ship's cat. He was a stray black cat who joined ship

at Chatham as a HO only rating and was "adopted" by a Petty Officer at

the end of the war. Alan Witton: "Both dad and E-Boat were on board for his entire time with HMS Woolston so she went to Archangel and Sicily". He certainly deserved a medal for all the hardships

he suffered but was popular on the lower deck though less so with the

CO. On one stormy day at sea Eboat lost his paw-hold, was swept

overboard and the cry, "cat overboard" rang out about the ship. The

captain on the bridge turned the ship round and, miraculously, Eboat

was rescued from the foaming-brine. He was frozen and exhausted and had

to be wrapped in a blanket and put in an oven to recover.

He was actually a "she" and led a lonesome life at sea and an attempt was made to find her a companion but the cat selected was a poor sailor, suffered dreadfully from sea-sickness under the hard-lying conditions endured by all the V&Ws and, at the first opportunity, jumped ship and Eboat was back on her own again. She was always a favourite with the sailors who made a great fuss of her but, sadly, I am still waiting for somebody to send me her photograph.

|

|

|

Sadly, their names are not recorded and their service certificates have not been traced.

I would like to acknowledge Frank Witton for the story of his old shipmate - you can read Frank's own story below

The men in HMS Woolston tell their stories

Frank Witton

|

|  |

|

|

|

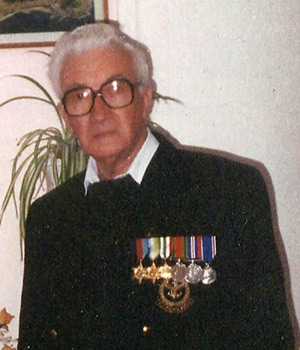

Frank Witton at his home in St Albans

in 2013 holding a print of a painting of HMS Woolston by Charles E. Turner who

spent some time on Woolston

Left: Alan Witton bought the ship's bell of HMS Woolston in North Carolina, USA, and flew to Britain in May 2019 to present it to his father on the anniversary of Woolston liberating Bergen

Right: Frank Witton holding one of the bronze tompions which covered the barrel of Woolston's 4.7 inch main guns, October 2019

Photographed by Bill Forster in St Albans where Frank was born 99 years ago

Cod, dried biscuits and rum for

Christmas Dinner on the stokers' Mess Deck, HMS Woolston, in 1942

The CO ordered two depth charges to be dropped and they lowered

a boat to collect the cod covering the sea

Neil O'Rouke from Glasgow is centre nearest the camera, Bill Perry

holds a

binnacle lamp and Jack Boore and "Spider" Kelly

are seated holding the keg of rum

Also in the photograph are "Smokey" Meadows and Ronnie Barnes

Courtesy of Frank Witton

The Coxon presents a silver teapot as

a wedding gift to First Lieutenant Bingham on HMS Woolston

Bill

Perry, Stoker, is second left and "Smokey" Meadows is on Lt Bingham's

left

Courtesy of Frank Witton

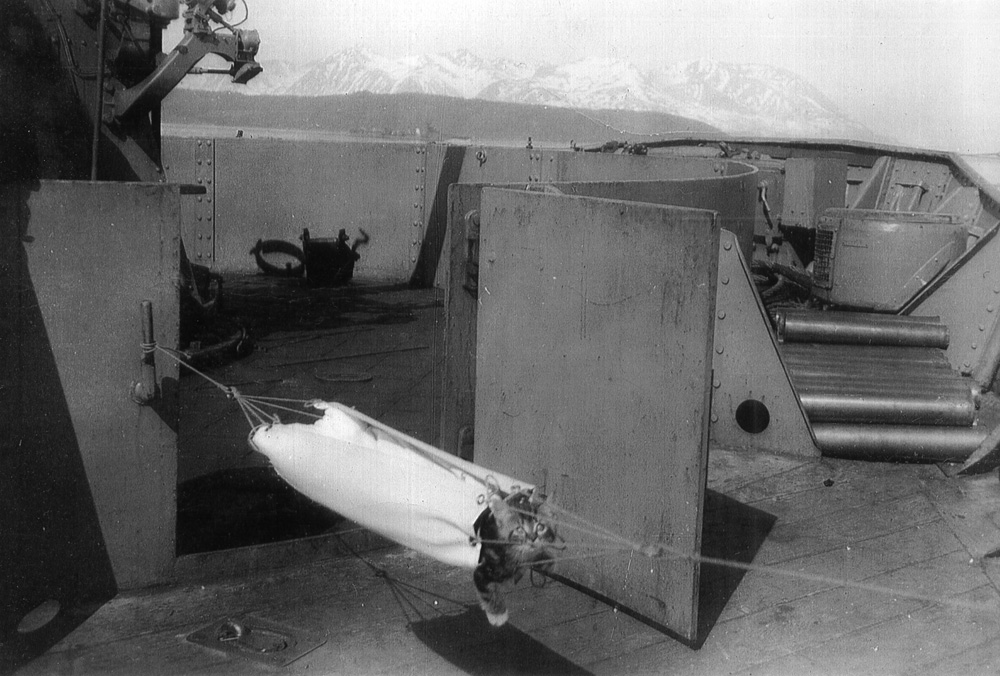

The dinghy of an allied airman rescued

by HMS Woolston

Courtesy of Frank Witton

Bill Forster recorded an interview with

Frank Witton at his home in St Albans in 2013

You can click on the link to listen to Frank describe his wartime service on HMS Woolston

The recording is on the website of the Imperial War Museum

Jack Boore tells his story on the BBC Peoples War web site: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/08/a2070208.shtml

I

spent my nineteenth birthday square bashing, not a very good day! Six

weeks

later came reality, posted to Royal Naval Barracks, Chatham. My

introduction to HMS Pembroke

came as a shock, thousands of sailors in barracks and on ships in the

dockyard, whistles blowing if you happened to be on the wrong side of

road, i.e. officers only area, yelling orders and doubling across

massive parade ground, fire fighting school, gas school, working in

boiler or engine rooms that were on the ships in dockyard and many more

tasks I never dreamed of.

I

spent my nineteenth birthday square bashing, not a very good day! Six

weeks

later came reality, posted to Royal Naval Barracks, Chatham. My

introduction to HMS Pembroke

came as a shock, thousands of sailors in barracks and on ships in the

dockyard, whistles blowing if you happened to be on the wrong side of

road, i.e. officers only area, yelling orders and doubling across

massive parade ground, fire fighting school, gas school, working in

boiler or engine rooms that were on the ships in dockyard and many more

tasks I never dreamed of.

After

this chaotic routine I was posted to a mine sweeper at

Grimsby. The boat was in the midst of a refit, pipes wires and hoses

cluttered the decks, my vision of a sleek modern destroyer or cruiser

was shattered, the ship was filthy, so, as you can imagine I was not a

happy sailor. Four days later the German air force bombed Grimsby naval

area, a bomb fell next to the ship causing damage so, once again pack

bag and hammock and return to the navy barracks at Chatham. That was

the

only time in my life that I was pleased to see the Germans. A few weeks

later ordered to drafting office, five of us were posted to HMS Woolston,

a 1917 destroyer based in Scotland, so I packed my kitbag and hammock

and was off once more. We travelled all night and arrived at

Inverkeithing the next day.

HMS

Woolston was at sea and we

were put onboard HMS Cochrane,

a depot ship in Rosyth. A few days’ later plans were changed, HMS Vortigern

was to be my assignment; I packed my worldly possessions and went to

Vortigern, unpacked my gear

and settled down in my new home (so I

thought). A few days’ later plans were changed again!!! HMS Woolston arrived in harbour, lots

of activity in harbour, ships getting ready urgently to go to sea. I

was ordered to join HMS Woolston,

once again I packed my gear and went aboard my original ship. We were

topped up with oil and ammunition.

"The

Dustmen in a group on a windy day": the Stokers after a boiler clean holding the ship's crest

The photograph includes:

"Smokey" Meadows (2), "Flash" Bowman (11), Ronnie Barnes (10), Frank

Witton (9), Sid

Winch (8), Stan Bister (7), Jack Boore (5) and Bill Perry (3) plus

Frederick Alexander

MacIver, A PO Supplies (4), who shared their Mess

Left: Jack Boore home on leave with

his parents, Fred and Liz Boore, and his brother Albert home from Burma

Courtesy of John Boore

The German battleship Tirpitz had left her base in Norway and all available destroyers in our area were dispatched to intercept her. We then began a chase at full speed up into arctic waters. Not a nice initiation into life in the Royal Navy (the thought of Bear Island still makes me shiver). Fortunately we never sighted the Tirpitz, apparently she got information about a fleet at sea to intercept her and Tirpitz, to our relief returned to Norway.

Shortly after our return to Rosyth we heard the tragic news that HMS Vortigern had been torpedoed by

German E-boats off the East coast and out of a crew of 212 only 12

survived. Lady luck was with me.

Sixty nine V&W Class destroyers were built during the First

World War, the ships' names all began with V or W. Modesty and privacy

was

forgotten as soon as you arrived on these ships, washing facilities

consisted of five hand basins in a room no bigger than a broom

cupboard, and toilets were five stalls (no doors) for about 160

ratings,

fortunately being engine room branch our clothing at sea was minimal

i.e. a

boiler suit over our underwear. Washing was done in a

bucket and put to dry in the boiler room above the boilers. The seamen

often never took their clothes off on putting to sea.

Life

was

horrendous, trying to get along the deck to your place of duty,

boiler or engine room during rough seas, or trying to have a meal when

sometimes the side of the ship was above your head was beyond

description. The stokers' mess deck was forward on ship, down a round

hatch about 36” diameter, twenty-two ate and slept in an area no bigger

than an

ordinary living room, if action stations sounded there was a mad rush

to get out as soon as possible. When in northern waters condensation

poured down the side of the ship,

giving permanent damp conditions , if in the Mediterranean area

the air conditioning was insufficient to keep cool, so one went from

one hell to another, it wasn’t unusual to be in Arctic waters one month

and then in the Mediterranean a month later.

HMS Woolston was my home

for

three years. Atlantic convoys, Arctic, North Sea Convoys, patrols in

Northern waters, Mediterranean, North Africa, Italy and the Sicily

Invasion. Joining as a 2nd class stoker on 2/- a day (10p),

leaving as a Leading Stoker. I returned to Chatham and then got posted

to HMS Suffolk

a 10,000 ton cruiser going out to Australia. War ended as did my four

and a half years service in the Royal Navy. For my efforts I got £83.

Jack Boore was 90 when he died in March 2013 and

never forgot his time on HMS Woolston

His son John followed him into the

Royal Navy and retired as a Chief Petty Officer after 25 years service

HARD LYING

Conditions on V & W Class

destroyers were so bad in rough weather that the men who served on them

were paid hard-lying money. These stories by veterans who served on

HMS Woolston were published in Hard Lying,

the magazine of the V & W Destroyer Association and republished in

2005 by the Chairman of the Association,

Clifford ("Stormy") Fairweather, in the book of the same name which is

now out of print. They are reproduced here by kind permission of

Clifford Fairweather and his publisher, Avalon Associates. Copyright

remains with the authors and

photographers who are credited where known.

G Hutchinson describes conditions on HMS Woolston

"On

the 15th July 1944 I was posted to HMS Pembroke

to await my first sea posting. I purchased a gold wire

winged flash of lightning to sew on the right arm of my best Naval suit

to indicate that I had now passed out as a R.A.D.A.R. Operator.

Although not permitted in peace time, the ‘in' thing for the war time

sailors was to be 'tiddly'. This meant, first of all to form a near

'tiddly' bow on the cap band by sewing a small button in the centre of

the bow, and instead of wearing the bow over the left ear as per

regulations it would he next to the HMS on the hat band and whilst on

leave the hat would be worn on the back of the head, something that you

would not dare do whilst in barracks.

Next the collar, with the three white stripes attended to, the issue

collar was dark blue, so we would bleach it to attain a lighter blue,

then you did not look like a 'sprog' who had just joined, and to give

the impression that you had served in some warmer climes and your

collar had been bleached by the sun. The tunic issue had a distinct 'V’

cut in the front which we cut to a 'U’ shape, and the silk neck piece

would be tied in a 'tiddly' bow at the front. The tunic was also

machined in at the waist to give a tighter fit. The bell bottom

trousers when issued would have 22 inch bottoms, these would have a 4

inch gusset in each leg to give a 26 inch bottom, then to finish off

the trousers would be given a good press with seven horizontal creases.

Those who could afford to would go to a naval tailor and have all these

modifications carried out professionally, then you would keep your

'tiddly suit' for going ashore or on leave only.

Whilst in Chatham barracks we were kept busy square bashing, peeling

spuds, mess cleaning, white line washing and generally having our

bodies and minds occupied. Walking across Chatham parade ground was not

permitted, everything had to be done at the double, otherwise it was at

your own peril and you would find yourself with stoppage of pay or

stoppage of leave.

I enjoyed some weekend leave whilst there, until I was posted to HMS Woolston

at Rosyth dockyard on the 24th September. I caught the train from Kings

Cross to Waverley station Edinburgh. Struggling with my kit bag and

hammock and weekend case I caught the next train to Inverkeithing,

seeing, and crossing the Forth Bridge tor the first time. When I

finally arrived at Rosyth dockyard I had to catch a Naval tender to the

Woolston who was anchored in

mid stream. I was accompanied by another ordinary seaman, Roy Cantwell.

No sooner had we been detailed to the forward port mess deck, stowed

our kit bags and hammocks, when we were told that we could go ashore

until 230O; Roy and myself took up the offer, even though we had been

traveling all day, so back we went to Edinburgh. On our return we

found that we had to kip down on the port side lockers because there

was insufficient room to sling our hammocks.

Early next morning reveille was piped at about 0500 and after getting

dressed we had to muster with the other seamen on the forecastle port

side as an equal number, eight men, were lined up on the starboard side.

We weighed anchor or slipped the buoy. It was very calm, but I had not

yet found my sea legs and found it very difficult standing still as HMS

Woolston slowly made her way

under the Forth Bridge out into the Firth of Fourth and on in to the

North sea to escort a convoy going South. For the next three days I was

seasick and did not feel too good, as a

matter of fact I wished that I had never joined. Some of my mess mates

did not mind, because they helped themselves to my rations.

Woolston was an old V&W destroyer built in 1918 by Thornycrofts,

her recognition and pennant number which was L49 was painted on her

sides just forward of the break in the forecastle.

There was a steam capstan in the mess deck and for this

inconvenience

we were entitled to an extra I/- a day classified as Hard Lying money.

The stokers and artificers mess was just below the seamen's mess. Just

forward of the break in forecastle and between the port and

starboard gangways was situated a small cooks galley, two members from

each mess would prepare the food and take it to the galley for the cook

to do his duty. The heads (toilets) and washrooms were situated

between the bulkheads

from the break of the forecastle to the mess decks. You could not

afford to be shy when using the toilets, because the partition between

the pans were so low that you could pass the time of day with you

'oppo' sitting on the next pan. The officers’ quarters and wardroom

were situated aft.

HMS Woolston was armed with

twin four-inch gun turrets fore and aft coupled with rocket launchers.

On port and starboard amidships were single Bofor guns. For submarine

warfare there were depth charge rollers astern and depth charge

throwers on both starboard and port quarters. There was an Asdic set

plus two radar sets, one amidships and one just above the bridge.

Invariably there would be three escort vessels on patrol and

occasionally four. Sometimes we would have the old American four

stackers which had been transferred under the Lend Lease Agreement.

During theses escort duties I would spend my watch on the midship radar

set. This set did

not have a cathode ray tube which showed a circular sweep. Instead it

depicted echo's in a straight line with blips bobbing up and down. One

could distinguish between low flying aircraft and ships. I would also

do a watch on the forward gun turret. In the winter, one of the crew

would go down to the galley and bring back a jug of 'Kye'. It was a

very thick chocolate drink which was made from scraping a solid block

of this special chocolate into a 'fanny' and adding water, then brought

to the boil, depending on who made it, it could be thick enough to

stand a spoon up in it.

At times we would have a little quiet sing-song among the gun crew, but

we would get a very curt command from the bridge if we raised our

voices too high. It was different when I was on the radar set, for I

would be alone for

four hours, just watching the echo's bobbing up an down on the screen

and only reporting if there was anything suspect occurring.

The washing of clothes or 'dhobeying' would be done in a bucket and was

either hung amidships between the two smoke stacks or hung down in the

engine room to dry. At sea we were permitted to wear overalls as rig of

the day, with

leather sea boots which reached up to the knee and thick white sea boot

stockings which were turned over the top of the sea boots, but as soon

as we sailed into harbour it was back to Naval uniform.

It could be very cold on convoy and if the weather was bad, as it often

was, the heavy seas would wash over the destroyers low deck line from

the break in the forecastle to the stern. I was fortunate to be one of

those recipients of one of the lambs wool lined leather coats donated

by South Africa. Also in rough weather, life-lines would be rigged from

the break in the forecastle to the stern. On these lines would be short

lengths of rope with an eye splice and thimble, so that anyone walking

along the deck could do so with reasonable safety.

There were times when the convoy would come to a complete standstill

due to thick fog. The escort vessels had radar, but not all the

merchant ships were so well equipped, I can remember one day when I was

on duty on the forward gun turret, in one of the lay-to situations when

a submarine

conning tower just slid past our bows. I can only assume that it was

one of ours. On other occasions the nearness of the enemy became was

plain to see. Action stations would be sounded and then some

unfortunate merchant ship would receive the full force of an exploding

torpedo and within minutes would be going down to the bottom. Sometimes

action stations were not sounded until the first torpedo had struck. In

either cases it would be full steam ahead and as soon as the depth

charges had been set, they were either rolled off the stem or fired

from the quarter throwers.

From the time I joined the Woolston

to the end of the war with Germany I think we only had one possible

sinking of a U-boat. We saw oil and clothing come to the surface,

but as that was a ploy played by both sides to mislead the attacking

surface ships, it could not be classified as a kill only a probable.

When we eventually returned to the mess deck, we would find that the

enormous pressure of the exploding depth charges had stressed the

ship’s riveted plates and she had let in water. Another consequence of

depth charge explosions were that some of the hammock slinging bars

would snap and some of the matelot's would have to find somewhere else

to sleep. I had to wait four or five weeks before I was allocated a

berth when one of my shipmates was drafted off the ship. The hammocks

were so closely slung that we were virtually in one large swaying bed.

To avoid breathing each others breath we used to sleep alternately head

to foot.

If there happened to be action stations during the night, we would

immediately come awake, grab some clothes and run like mad to our

action stations. On one occasion a German E-boat sped up between the

lines of the merchant ships, firing its torpedo's and guns. There was a

bit of a 'ding-dong', but no major hit, just shell holes in the ships

funnels and side. Sometimes the rough sea would free mines from their

moorings and these

floating hazards would give the gun crews some extra practice.

We were granted four free travel warrants each year, so when the Woolston

went into Leith dockyard for a refit I used one for some home leave.

The train journey from Edinburgh took some 8 to 9 hours overnight, the

train was always completely crowded with service personnel going on or

returning from leave. When the train pulled into Kings Cross it was an

experience to see the number of service men who had no ticket, with

just one or two ticket collectors on duty, they had no chance to slop

the surge of passengers, some would jump over the barriers or would

offer any piece of cardboard that looked like a ticket. Most of the

ticket collectors could not care less as they probably had some member

of their family serving in the forces anyway. Some of the servicemen

would just push their way through the barrier without offering tickets

or fare.

In early May 1945 HMS Woolston

with another six destroyers left Rosyth and headed towards Norway.

Memories of HMS Woolston by A.M. Lee

An anonymous contribution to Hard Lying, the anthology of articles first published in the newsletter of the V & W Destroyer Association

"Woolston was among the Naval vessels that took part in the invasion of Sicily, and celebrated her birthday by escorting a convoy to the landing beaches. Once the ships were safely in, her job was to patrol for lurking U-boats and stand by to give a blazing reception to enemy aircraft which might try to interfere with the convoy.